What follows is translated from an original cookbook titled “Östliche Speisen nach deutscher Art” (Eastern Dishes in German Style), with recipes tested and compiled by the Oberkommando des Heeres. It was published during the war by Alfred H. Linde Verlag in Berlin and was intended to be used as a field cookbook for German soldiers in the East. This section entitled “Improvement of Cold Fare” is particularly interesting and useful for living historians, as it gives insight into some easy ways that German soldiers may have prepared canned meat and other field rations.

“Improvement of Cold Fare

To stimulate the appetite, and especially during the warm season, cold fare should be prepared in a flavorful way.

The following instructions can be combined with each other to be adapted in various ways.

Bread spread from canned meat

300 g beef (canned)

100 g sardines

100 g tomato paste

Finely chop the beef and sardines, add the tomato paste and prepare as a pate.

Note: If the mixture is too dry, add some butter, margarine or oil.

Fleischsalat (Meat Salad)

400 g canned meat

200 g diced tomatoes (fresh or canned)

100 g finely chopped onions

Vinegar, oil, salt, pepper

Cut up the meat, gently combine with the tomatoes and onions. Mix with a marinade of the oil, vinegar, salt and pepper.

Note: Bell peppers can be used as a substitute for the tomatoes.

Cold Meatballs with Potato Salad

To make fried meatballs from canned meat, the meat must be finely chopped and then air dried for a time. The meat is then seasoned with salt and pepper and well-mixed with flour. This can also be mixed with bread crumbs, soaked bread, finely chopped onions, egg or only egg white, or egg substitute. Mix everything well together and form into meatballs. Coat with flour or bread crumbs and fry in hot oil until cooked through.

For the potato salad, boil the potatoes with the skin on, peel while hot and slice. Immediately mix with a marinade of water and vinegar brought to a boil and seasoned with salt, pepper and finely chopped onions. Pour this over the hot potato slices and either shake or carefully mix until the salad is bound together.

Note: The salad can be refined with oil, finely chopped herbs or diced pickles.

Canned meat and sausage

Canned meat and sausage are particularly appetizing when fried and roasted together with finely chopped onions and tomatoes.

Canned sardine salad

Mix sardines for five potions with 200 g sliced tomatoes. Marinate with the oil from the sardines, 200 g finely chopped onions and lemon juice.

Note: If tomato paste is used, it should be mixed in to the marinade.

Ölsoldaten

Fry the sardines in their own oil while adding finely chopped onions. Drizzle with lemon juice as a dressing.

Canned sardines in the style of fried herring

Fry the sardines and lay them in a pot. Make a marinade from vinegar, onions, salt, pepper, bay leaf and allspice, allow to cool and pour over the sardines.

Tuna fish in oil

Tuna fish in oil can be prepared just as the canned sardines.”

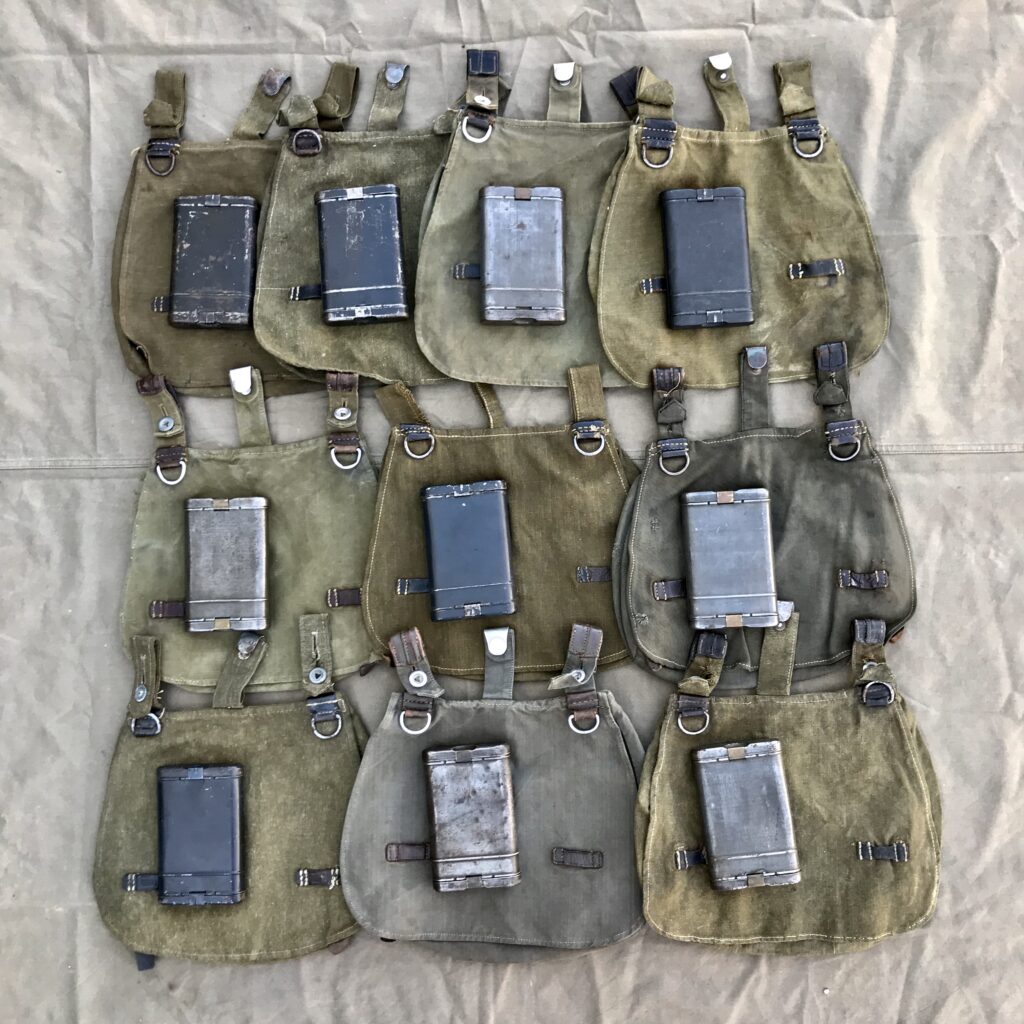

Note: For reference, a couple of pictures of original Wehrmacht-issue aluminum food cans. Here are two variations of a can that held fish or perhaps some other kind of meat. The one in front is stamped with a 1944 date code.

Here is a tin of Norwegian sardines, these are commonly recovered from former German positions. This one was found at Stalingrad.

For more information about steel and aluminum food cans issued to Wehrmacht soldiers, check out the fantastic reference “Rations of the German Wehrmacht in WWII” by Jim Pool and Tom Bock. Thanks to Peter Speiser for providing the original cookbook mentioned above.