This booket, “Gut flicken! Gut stopfen!” (Patch well! Darn well!), was part of a series published by the Reichsausschuss für Volkswirtschaftliche Aufklärung, in connection with the Reichsfrauenführung. It is undated but was released around 1937.

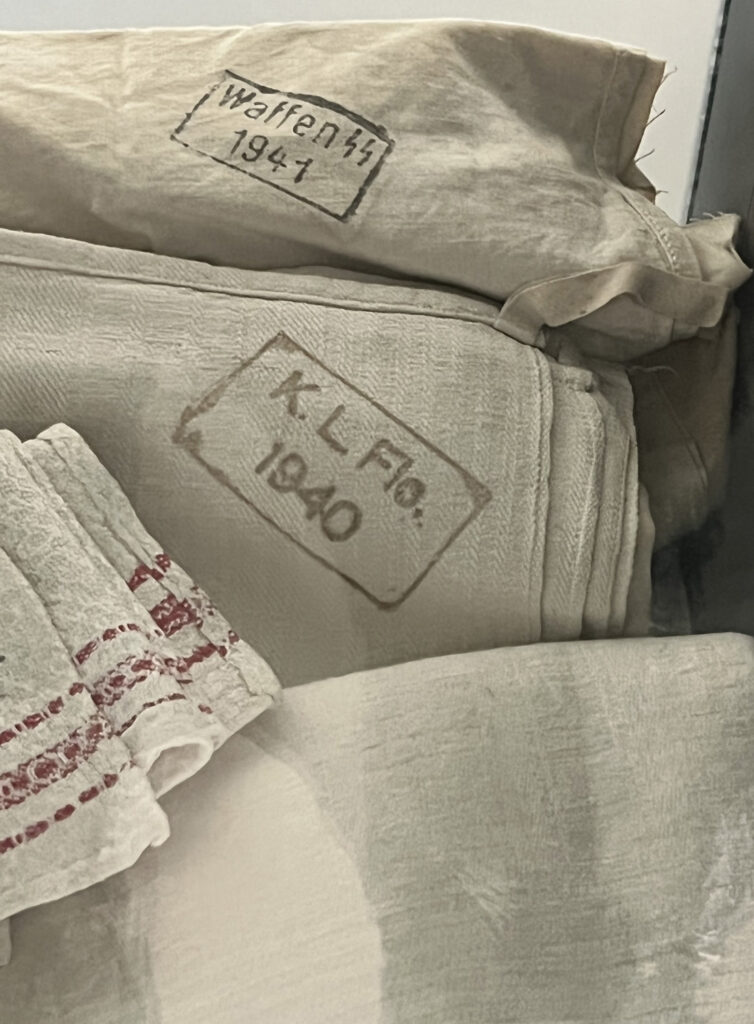

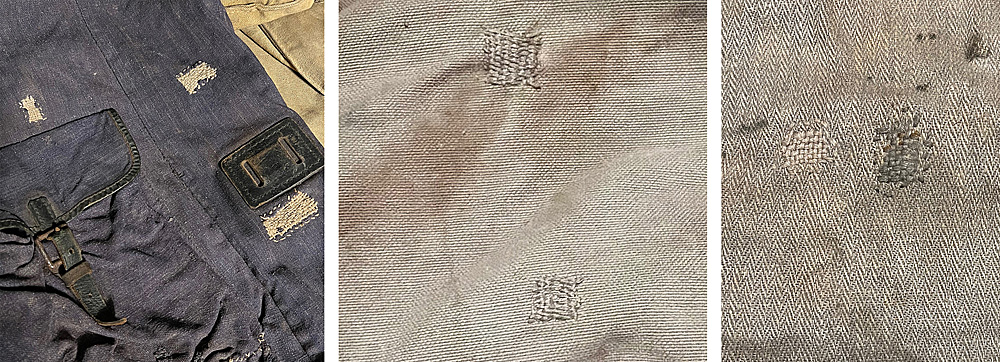

The book is intended for women, who were expected to be able to repair the clothing for all the members of the household. In that era, not only housewives would have been familiar with basic sewing and mending techniques. These were important skills in a time when clothing and fabric were more expensive, and people had less of it. Wehrmacht regulations stated that “every soldier must himself perform small repairs on the uniform and equipment items he was issued, as long as these do not require specialized craftsmanship knowledge to be repaired, for example replacing buttons, replacing hooks and eyes, sewing split seams.” These military issue socks were worn by German soldiers at the end of the war, at the time of surrender, and for some time afterward. They show extensive darning and patching repairs. These repairs were likely done by the soldiers themselves.

This soldier’s shirt also has been patched and darned.

Not only knit items were repaired by darning. Canvas equipment items such as rucksacks and clothing bags can be found with darned as well as patched repairs.

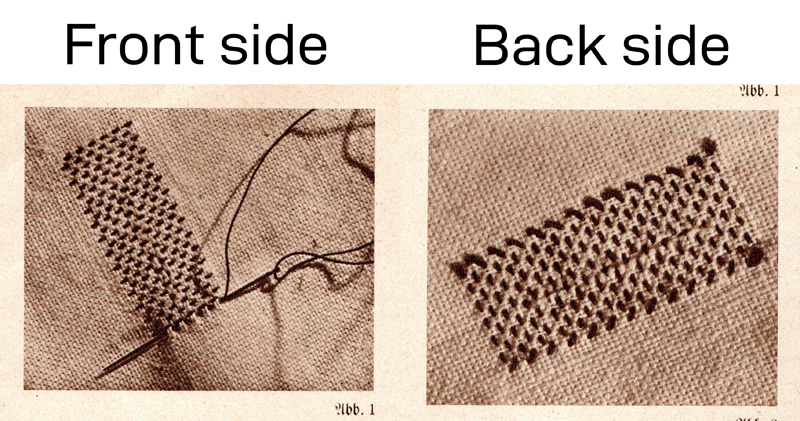

Let’s look at some of the repair techniques shown in the 1937 book. There is instruction on darning techniques. The book takes it for granted that the reader is already familiar with the basic concept of darning and instead gives some technical tips about best practices, including what kind of thread to use and how to approach repairs on different fabrics. For readers who are not familiar with darning, there are lots of instructional videos online that show how to do it; the darning tips in this book are much more readily understood with this background knowledge. This illustration shows a darned repair where the tear in the fabric ran parallel to the fabric’s weave. This type of repair can also be used for wool, it is noted in the book.

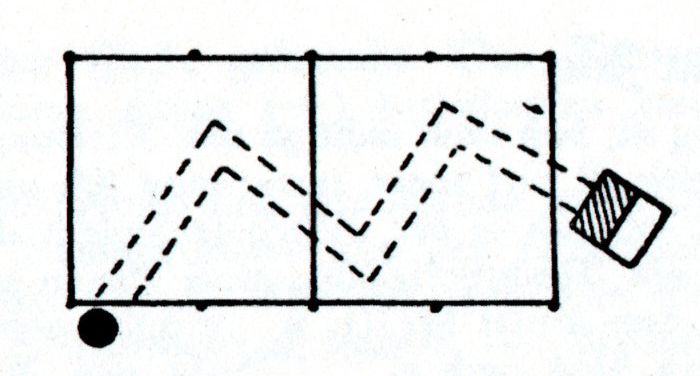

This illustration shows darned repairs to damage that runs diagonal to the weave of the fabric, and to an L-shaped tear. This style of darning, where the threads go in one direction and then are woven in a perpendicular way, is commonly seen on used items from that era.

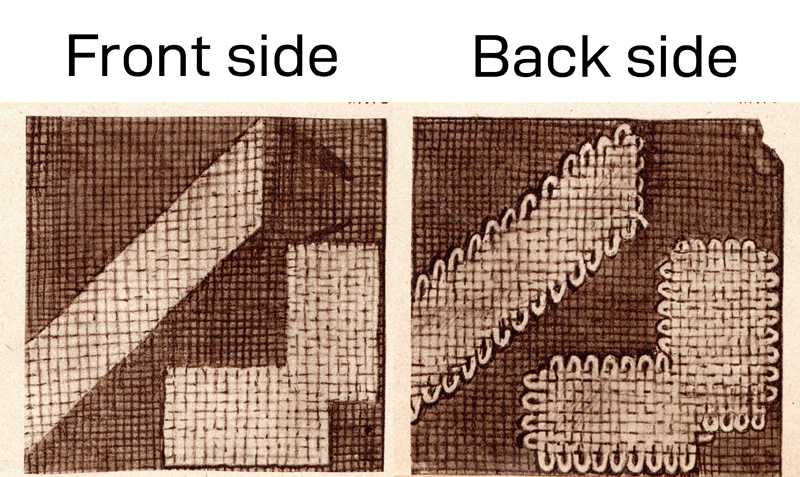

This is how holes in linen were to be repaired, with darning.

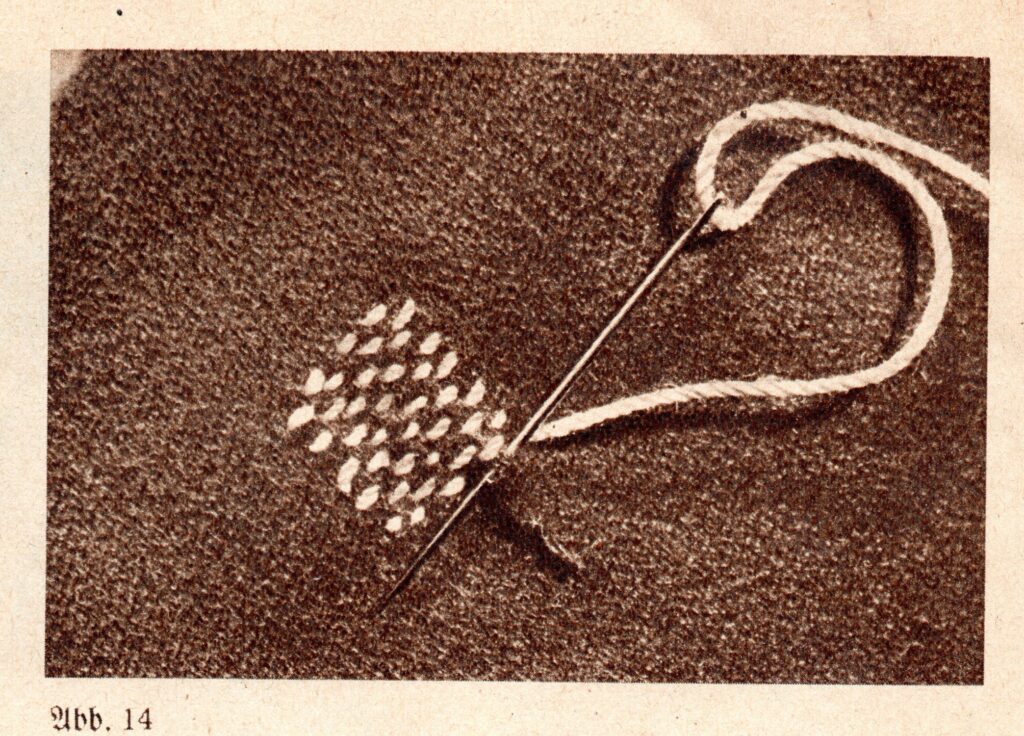

This is a method of darning a rip in wool cloth, of the type used for WWII German uniforms. For the illustration, a thick, contrasting thread was used, to enable the viewer to easily see the technique. The book suggests women use much finer stuff- human hair.

The type of thread to be used for darning depended on the material being darned. Cotton fabric was to be darned with cotton thread or cotton yarn, because silk thread would not withstand being boiled when cotton clothing was cleaned. Silk fabric was darned with silk thread. Wool fabrics could be darned with silk or cotton, and heavy fabrics could be darned with linen.

Different repair methods were to be used for different types of clothing. A variety of patching styles were devised, which are illustrated in the book and which we will show below. Some of these techniques seem to have been more widely used than others. The book states that heavy outerwear could be repaired with sewn-on patches, sewn-in patches, or “pulled through” (durchgezogen) patches. Light outerwear could be repaired with “pulled through” patches or “couch stitch” (kordoniert) patches. Wool fabric could be repaired with “darned in” (eingestopft) patches.

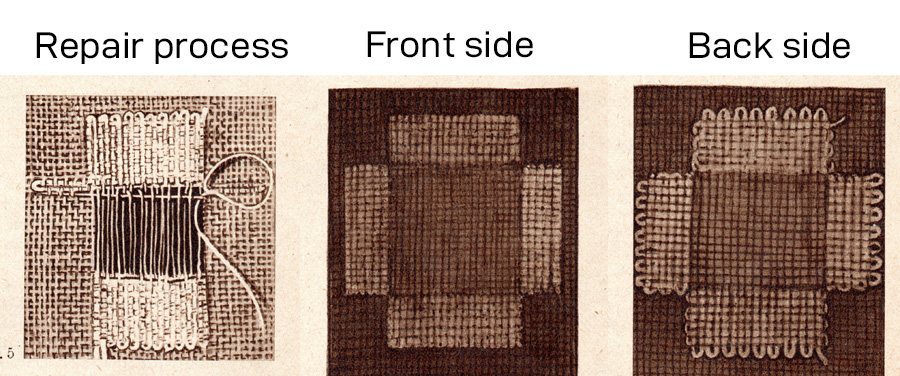

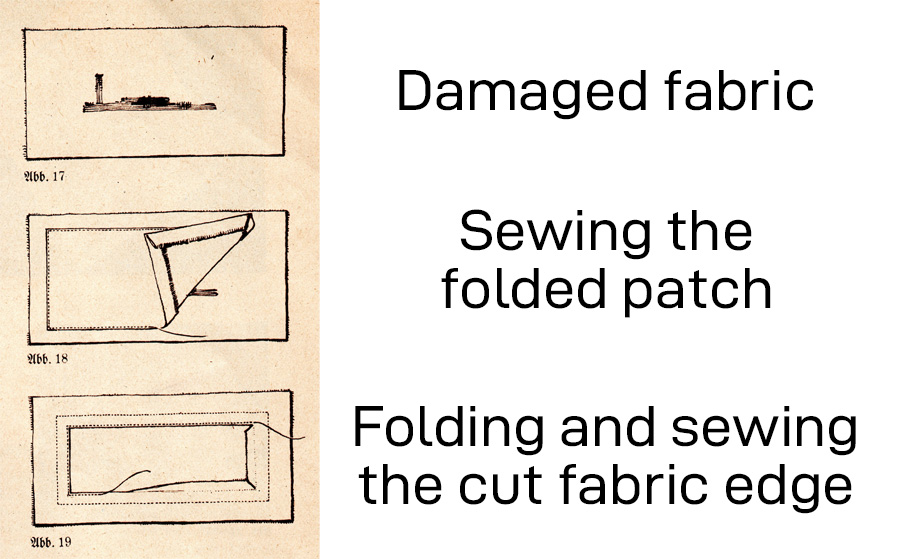

Sewn-on patches

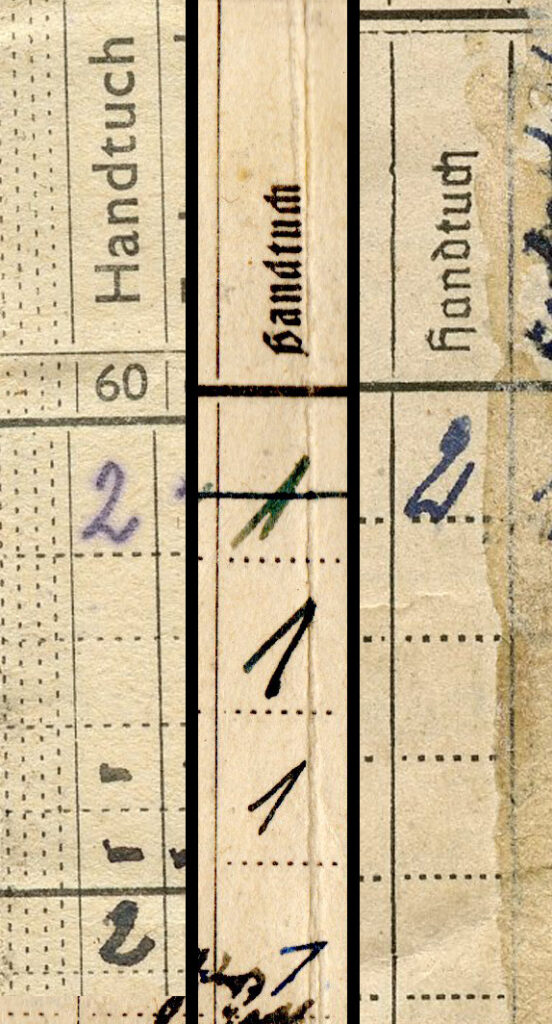

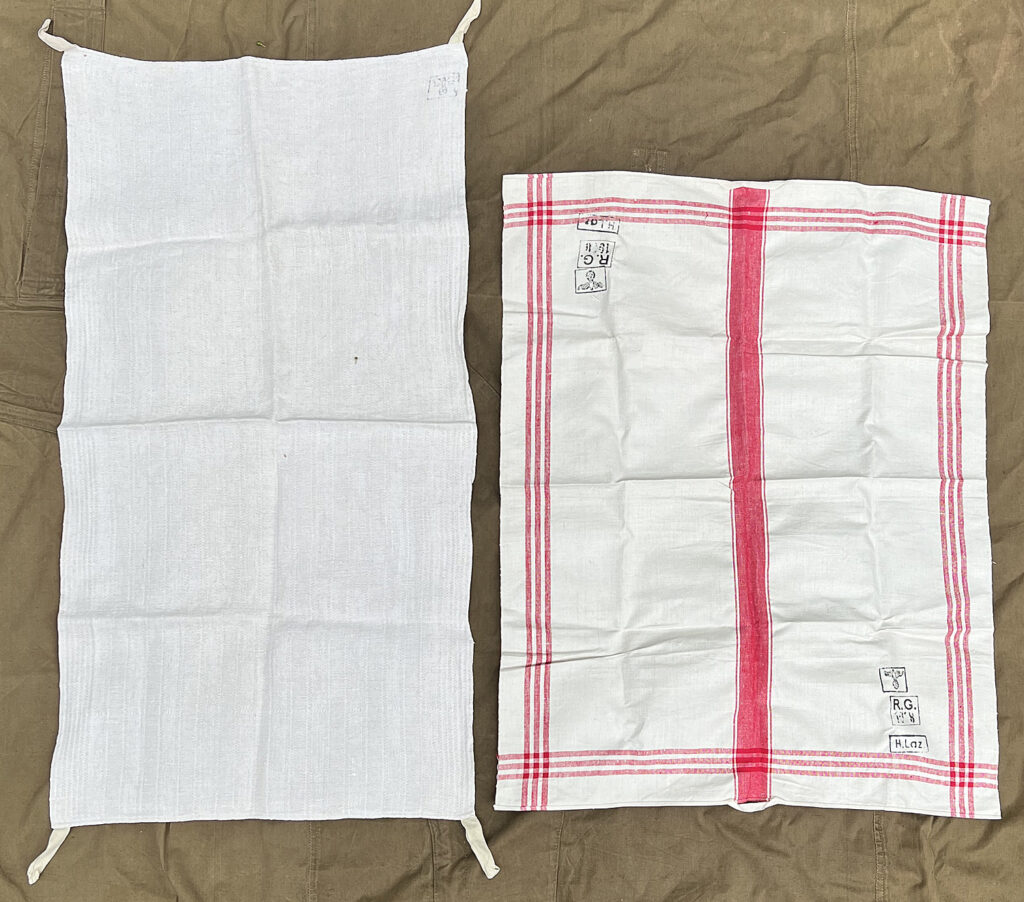

According to the book, this style of repair is easy to do and was often used. This was well-suited for fabric that was often stressed, such as bedding, hand towels, work clothes, skirts, etc. A square or rectangular patch would be folded and stitched over the damaged area. The damaged area would then be carefully cut away, with the cut 1.5 cm inside the patch line. The corners are then cut another 5 mm so that the cut edges of the fabric can be folded under, then stitched all the way around. This is not mentioned in the book, but this style of patch is commonly seen on Wehrmacht Zeltbahnen (shelter quarters).

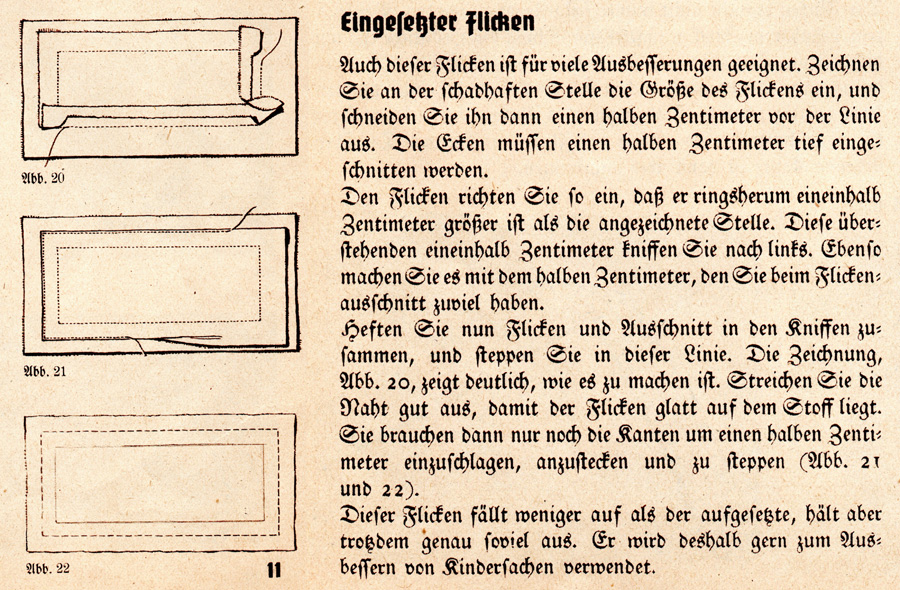

Sewn-in patches

This was a somewhat more challenging type of repair than the sewn-on patch. It failed less often than the sewn-on patch and was well-suited for children’s clothing. First, a line would be drawn around the damaged area, the size of the patch. Then the damaged area would be cut out 5 mm inside the line, with 5 mm cuts in the corners. The patch would then be applied, carefully folding as indicated in the illustrations.

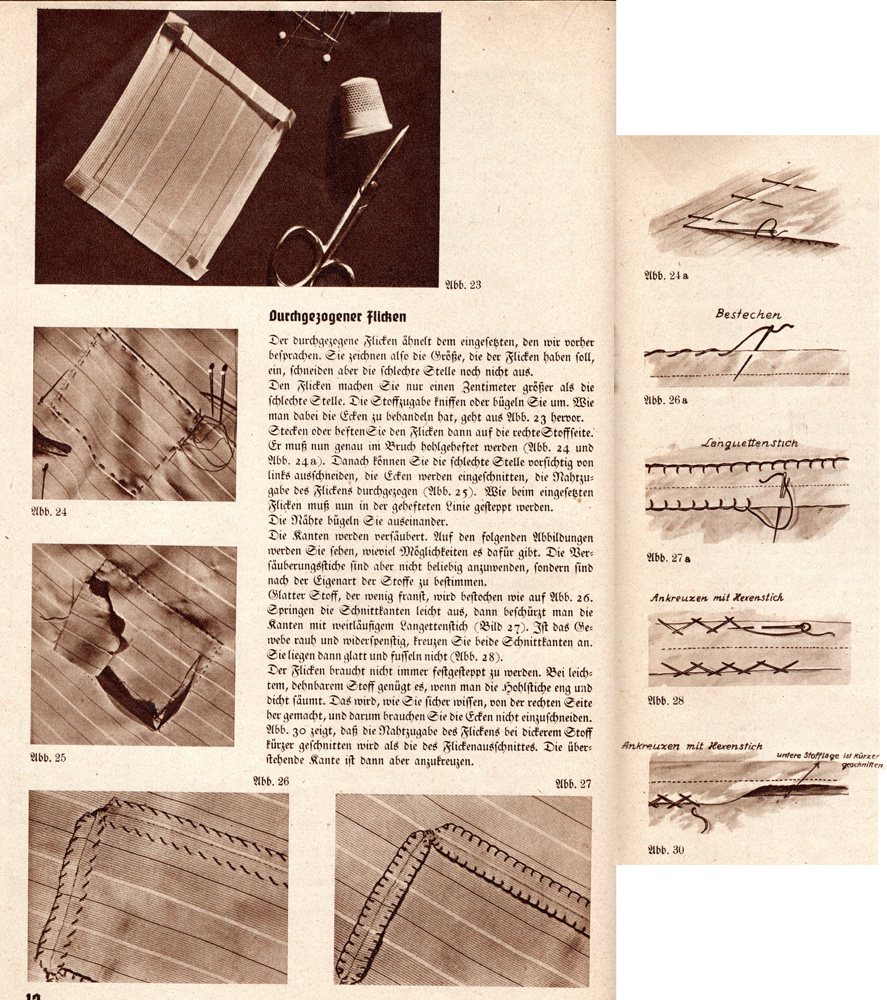

“Pulled through” patches

This was similar to the sewed-in patch but the damaged area was not cut away. This is not a style of repair that I can remember having seen on period items and may have been a relatively advanced technique.

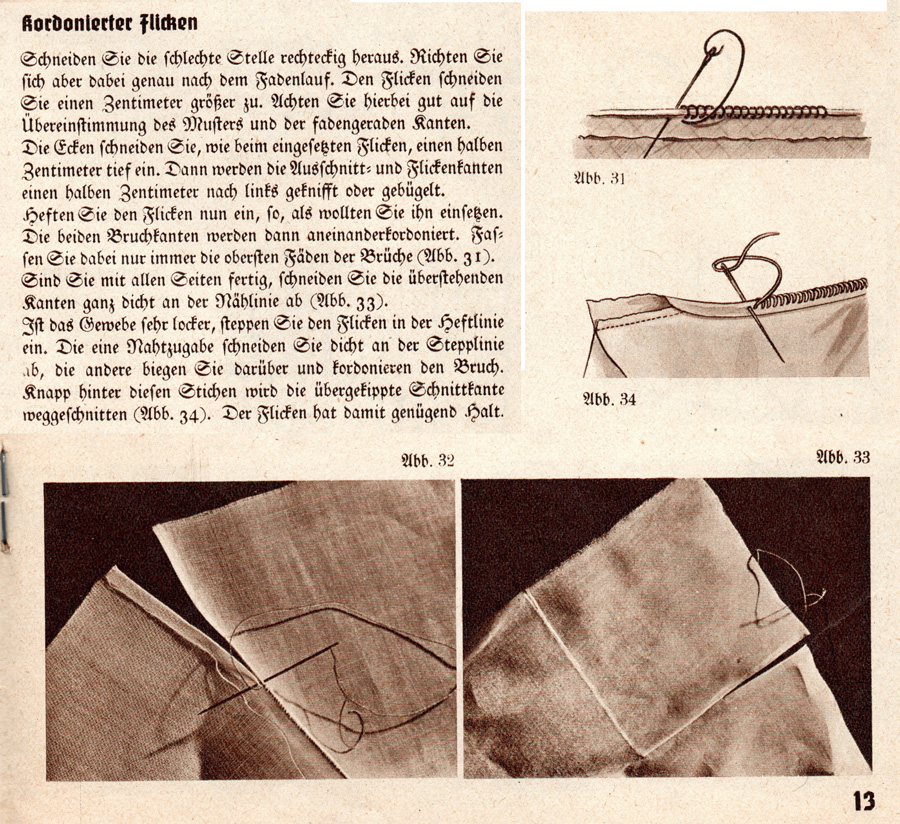

“Couch stitch” patches

This again is a style that I do not recall having seen used.

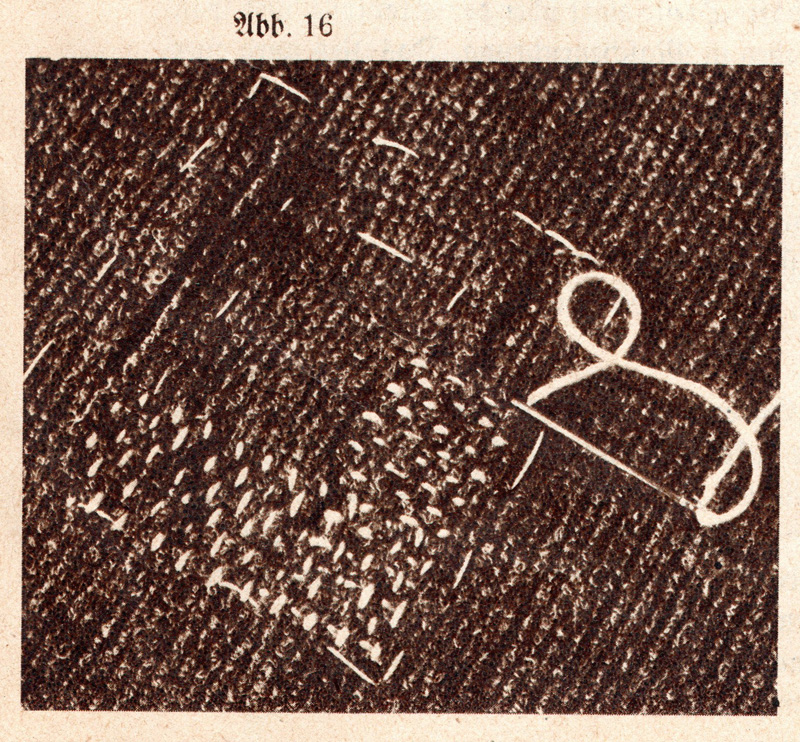

“Darned in” patches

For this style of repair, the damaged section of fabric would be cut away in a square or rectangular shape, carefully cutting along the weave of the fabric. A patch of the same fabric the item was made of would be cut exactly the size of the cut-out. The patch would be inserted, with the edges of the patch pressing against the cut-out edges all the way around. The edges would then be darned together. This could be done with wool fabric, taking into account the direction of the wool nap.

All of this information about darning and patching takes up the first 13 pages of this 24-page booklet. The rest of the book goes into detail about repairing knits and lace, restoring trousers, repairing armholes, replacing the upper parts of dresses, how to flip over collars of shirts, how to turn a worn-out shirt into a nightshirt, how to restore worn trouser cuffs, and more. Some of this would be considered tailoring, by modern standards. I think it is true to say that many skills that we regard as specialized and advanced today, were much more widespread in the past, when a sewing machine was an appliance found in most households.

The ability to mend clothing is valuable. A small hole, immediately darned, requires little effort and is often almost invisible. A quick repair to minor damage can prevent having to later make a choice between trying to repair major damage, or replacing the item.