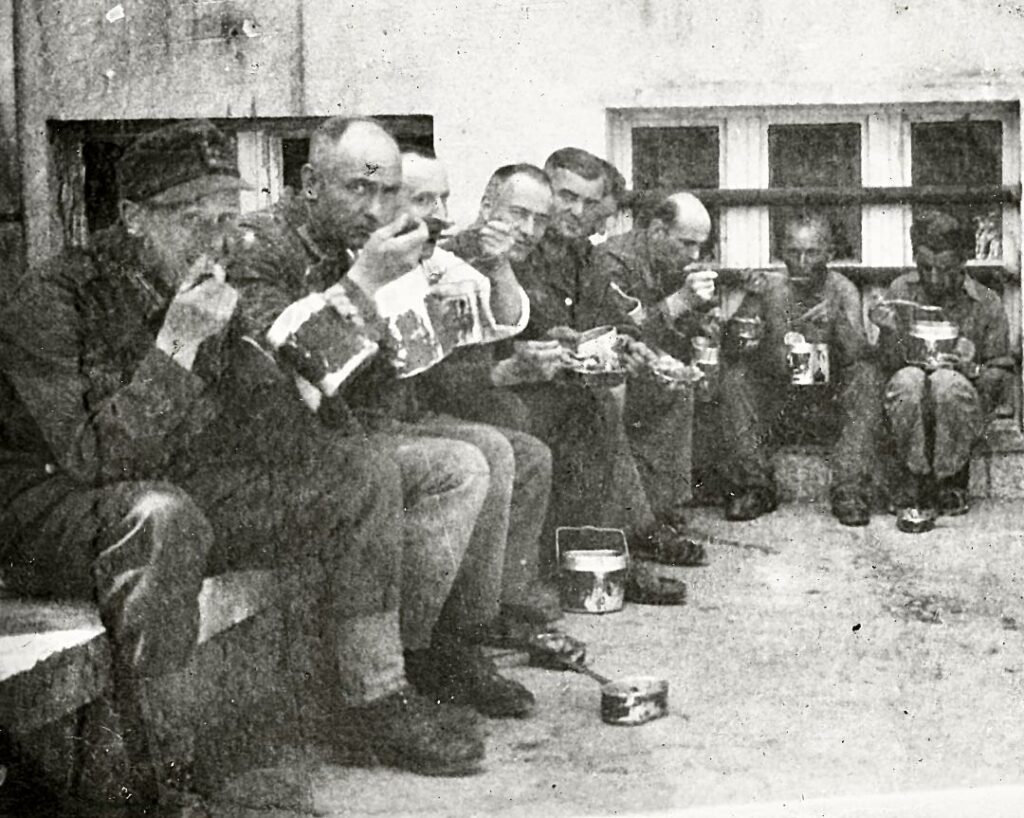

Typical German field fare relied heavily on easily prepared meals made with a limited range of ingredients. In many cases, issues with supply and availability of meat mandated the preparation of meals that used little meat, or were vegetarian. The 1942 cookbook “Fleischlose und Fleischarme Feldküchengerichte” (Vegetarian and Low-Meat Field Kitchen Meals) by Richard Schielicke gave tips on how to make hearty meals without relying on large quantities of meat. “Meals prepared with a sufficient quantity of meat, even when simply prepared, have in the hearty meat juices a good flavor basis that meatless and low-meat dishes lack. We must compensate for that, if of course only in part, through proper handling of the ingredients before cooking, better cooking methods, correct and appropriate use of particularly German seasonings, and the use of good, tasty Tunken (gravies).”

The 1941 cookbook “Die Feldküchengerichte” (The Field Kitchen Meals) gives the following instruction on making gravies.

“The basic ingredient is broth, to this is added a thickener, for example a roux (about 8 grams) or grated white bread (about 20 grams per 1/4 liter).

We will differentiate between dark and light gravies.

Light gravies consist of light broth and light roux. Dark gravies consist of dark broth and dark roux.

Gravies with flour as a thickener

a) Light basic gravy

Melt fat, and roast finely chopped onions in this for a short time. Add flour and cook for a few minutes until light yellow, fill with bone broth or meat broth and cook for 20 minutes. The gravy can be improved by the addition of milk.

Variations of light basic gravy:

Herb gravy: add aromatic herbs of all kinds, especially parsley, chervil, chives, also wild herbs.

Dill gravy: add dill

Chive gravy: add chives

Marjoram gravy: add marjoram

Mustard gravy: add mustard

Tomato gravy: add tomato paste or tomato powder

Bechamel sauce: offset the light gravy recipe with one-third milk

Horseradish gravy: Make Bechamel sauce and mix in grated horseradish

b) Dark basic gravy

Melt fat. Add flour and slowly roast until brown, constantly stirring. Add onions and brown for a short time. Fill with dark broth and cook 20 minutes.

Dark broth for filling:

Roast smaller bones with soup vegetables and boil for a few hours. If dark broth is not available, fill with light broth or hot water and improve with yeast extract or seasonings.

Variations of dark basic gravy:

Herb gravy: add herbs, especially marjoram, thyme

Pickle gravy: add pickles and pickle juice

Mustard gravy: add mustard

c) Gravies with grated white bread as a thickener

Cook grated white bread or Zwieback in the broth. In a pinch, it is enough to soak it and stir it into the boiling hot broth.

Flavoring ingredients are as with the light and dark gravies.”

“Die Feldküchengerichte” goes on to provide instructions for “Tunkenkartoffeln” (Gravy potatoes). “Peel boiled potatoes, slice, and heat in one of the light or dark gravies.” The book gives a list of potato meals that can be prepared simply by making the corresponding gravy and heating prepared potatoes in them:

“Tomato potatoes

Marjoram potatoes

Herb potatoes

Dill potatoes

Mustard potatoes, etc.“

The “Ten Rules for the Field Cook” mandated that field meals were to be cooked thick, not soupy. An ample portion of cooked potatoes in a rich and flavorful sauce is a hearty and filling meal that yields a lot of satisfaction and energy. Even without meat, it is heavy comfort food. Home cooks in wartime were also encouraged to make simple, easily cooked meals like this to save energy for war work, and to be thrifty with raw ingredients in a time of scarcity.

The photo at the start of this article shows potatoes in a light gravy with marjoram. Marjoram was not widely used in the USA until after WWII but it had a long history in Germany where it had over 10 different local common names. “Fleischlose und Fleischarme Feldküchengerichte” says that marjoram is “an excellent seasoning for savory gravies, legume and potato dishes, and the good, old pea soup is unthinkable without it.”