From “The Soviet Partisan Movement 1941-1944” by Edgar M. Howell.

A living history group in New England, USA, portraying WWII German Wehrmacht security troops.

From “The Soviet Partisan Movement 1941-1944” by Edgar M. Howell.

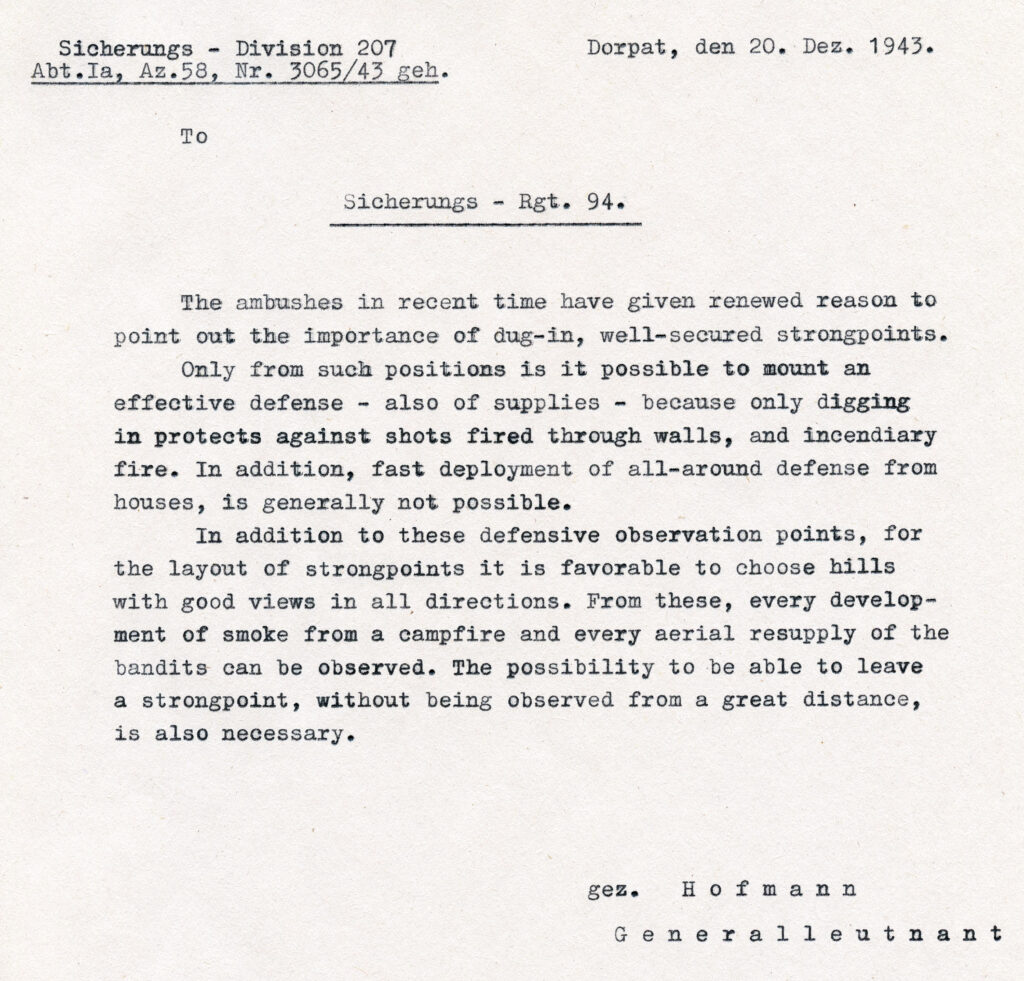

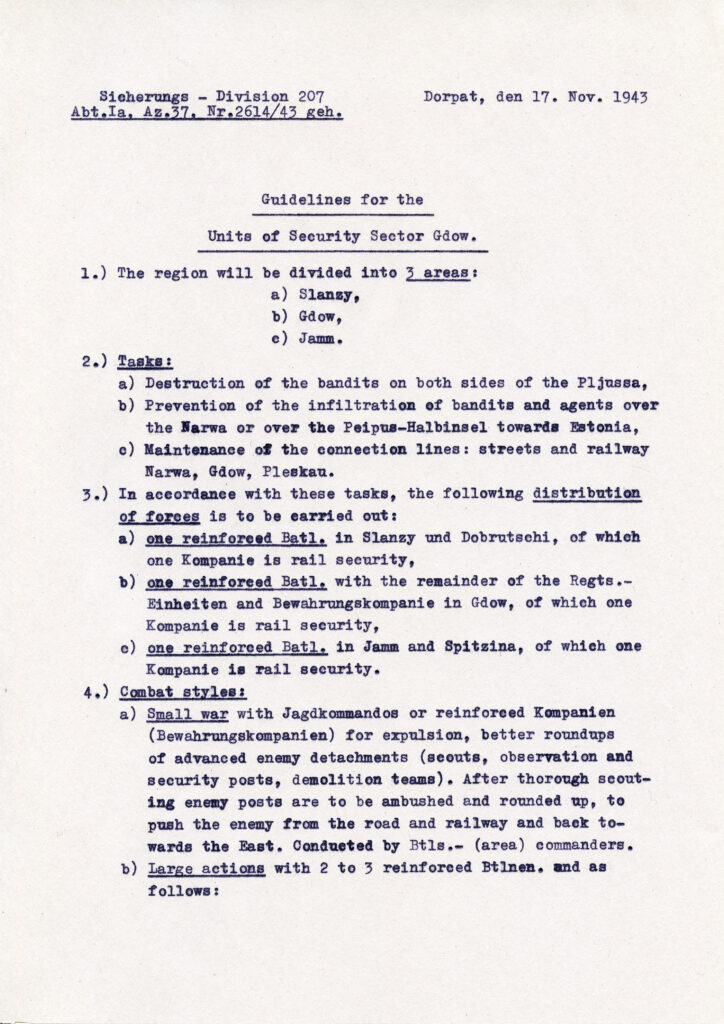

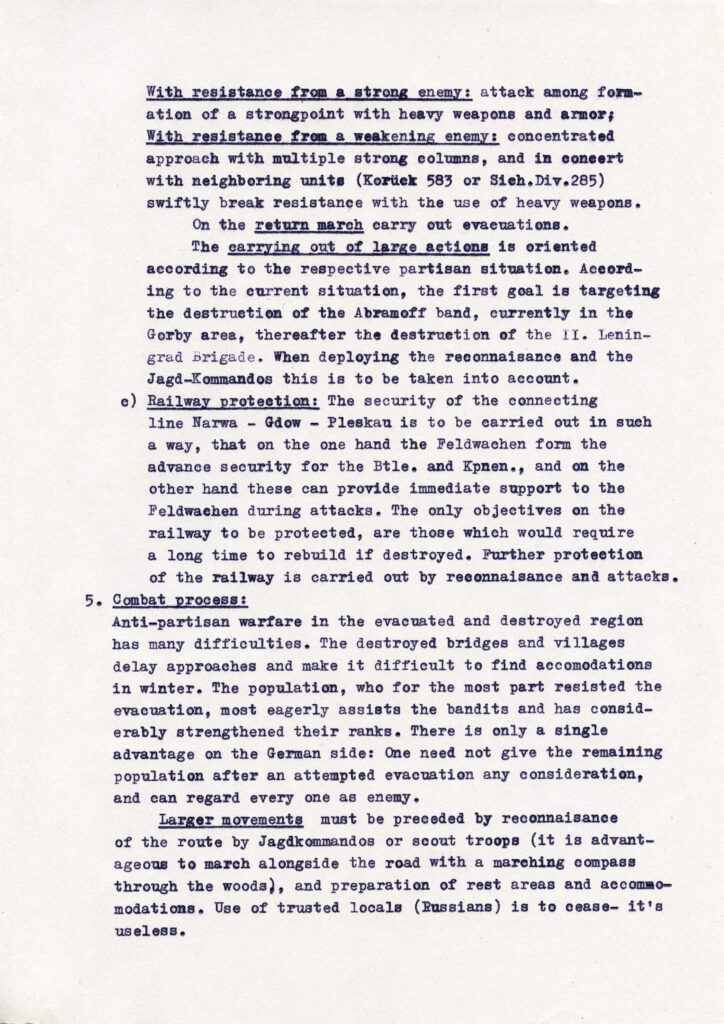

The following six page document is from the files of the 285. Sicherungs-Division. This was disseminated to all units of the 4. Panzergruppe in July, 1941. It is part of a combat manual for Soviet partisans, translated into German (and then by me into English). This document contains information about how partisan groups were organized in 1941, and how they were instructed to fight.

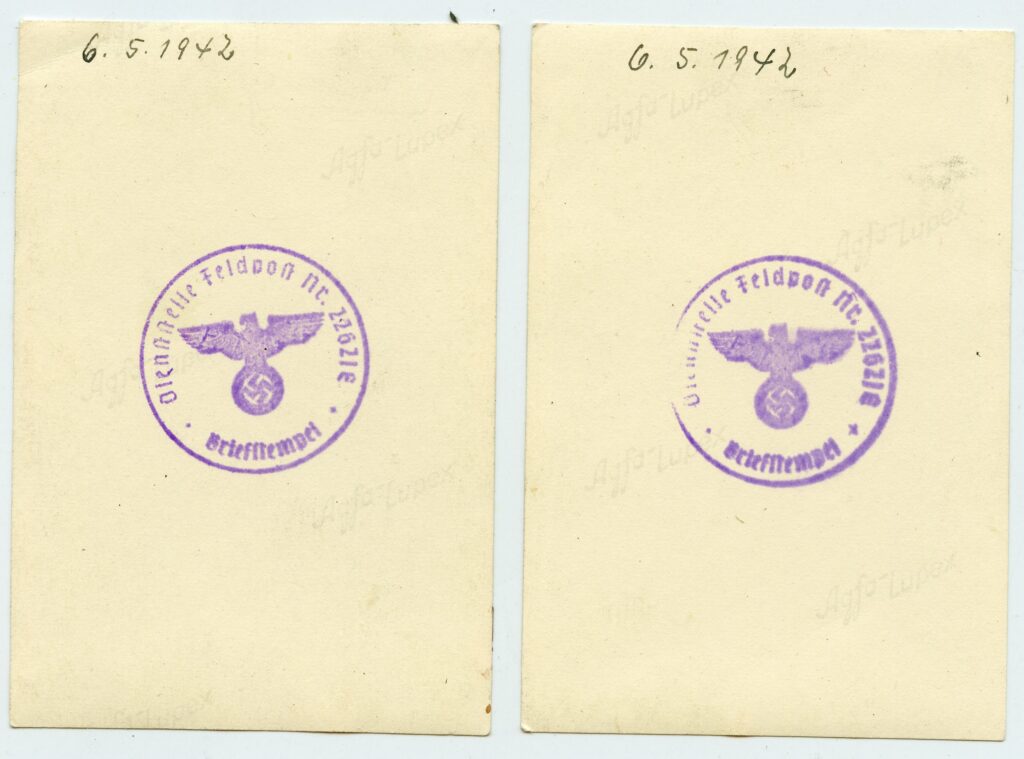

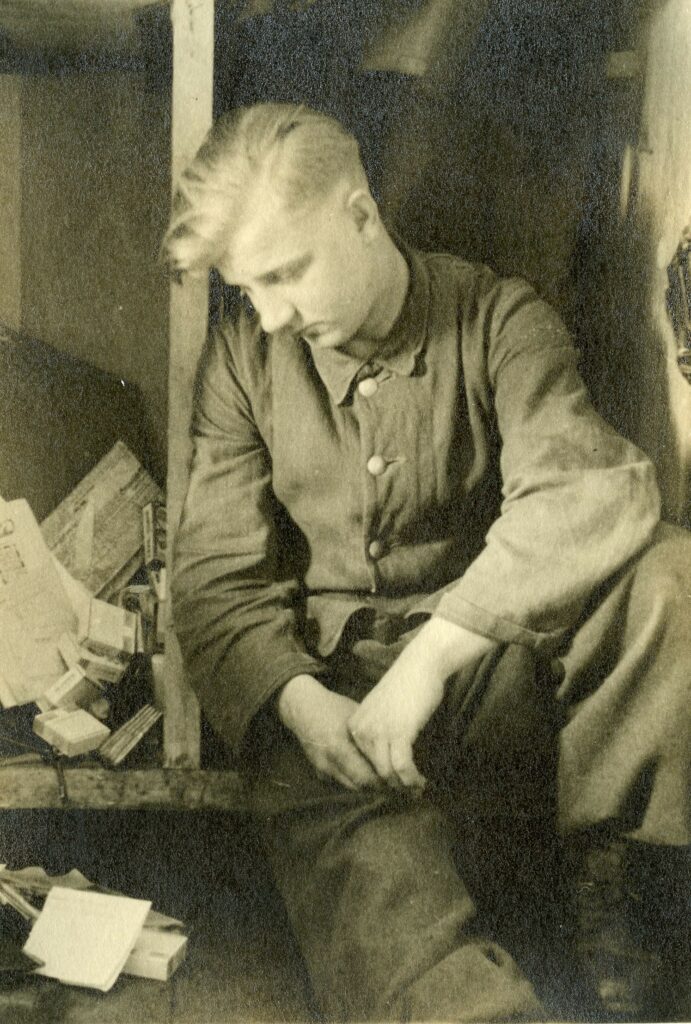

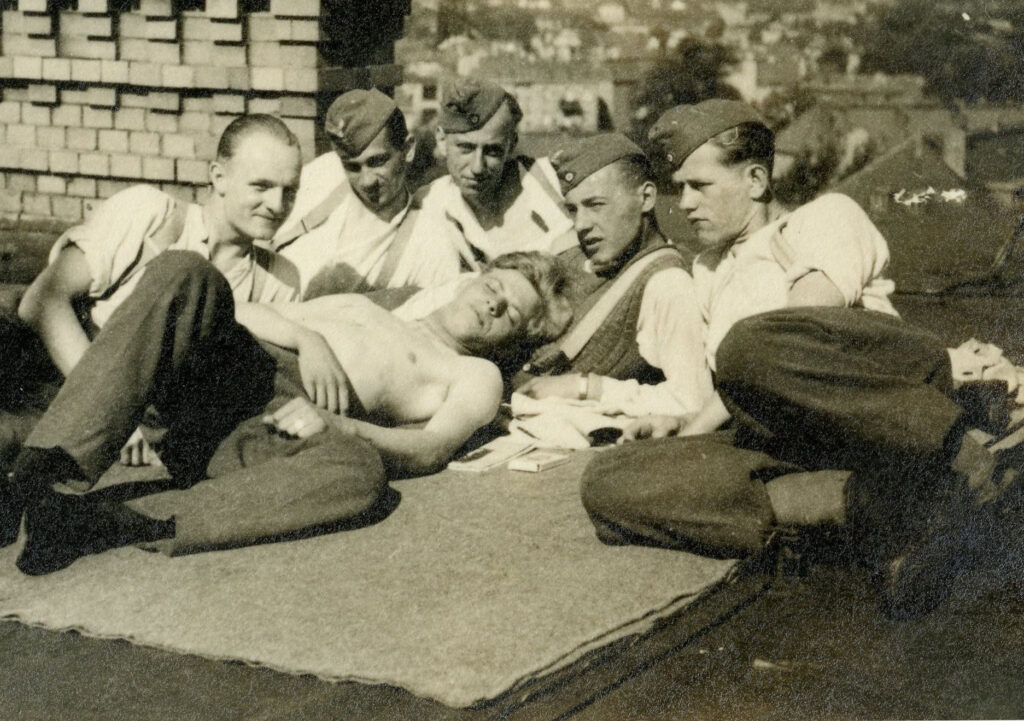

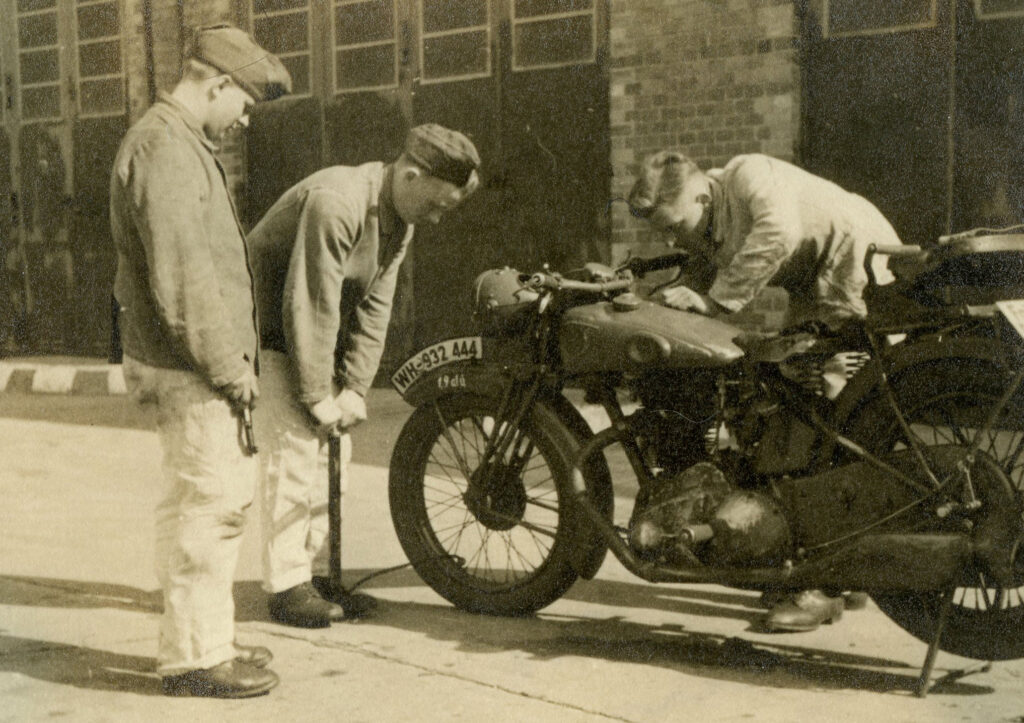

These private photos are dated May 6, 1942.

The unit ID and date are indicated by markings on the back of the photos. Feldpost number 22621E was at this time used by 4. Kompanie, Landesschützen-Bataillon 313.

In May on 1942, this unit was assigned to Korück 532 of the 9. Armee, part of Heeresgruppe Mitte which was at that time in central Russia.

The soldier in these photos wears a mixture of standard issue Wehrmacht gear together with obsolete and captured elements, a combination so typical for soldiers in Landesschützen and Sicherung units. The collar Litzen on his prewar M36 tunic are applied directly to the collar without backings, suggesting this is a reissued tunic with replaced insignia. The helmet is the standard issue Wehrmacht type with matte field gray paint, but the lace-up tall boots are an earlier, Reichswehr pattern. The Gewehr 98 is a WWI pattern rifle, here used with a corresponding 1909 pattern ammunition pouch, obsolete before the start of WWII. He is wearing a captured prewar Polish Tornister pack. Additional field gear visible in the photo includes a bayonet and entrenching tool, a gas mask canister with gas cape bag worn in the front in the early war style, a bread bag, and a Zeltbahn shelter quarter strapped to the Tornister. The weight of the equipment on the belt is carried by the internal suspenders inside the tunic. The field cap tucked into the belt is adorned with the white branch piping worn by Landesschützen units. The tunic is adorned with a single award, a civilian SA Sports Badge.

Many Landesschützen and Sicherung units were irregularly equipped in this manner, as they had a low supply priority. Even at the start of the war, Germany faced shortages of raw materials and other logistical hurdles that made it hard for them to equip the millions of men needed for their armies. Front line combat units got the best and newest material, while rear area units that also had an important role in maintaining order in the occupied areas got the short end of the stick. A May 1941 report in the war diary of the 281. Sicherungs-Division described the situation: “The “alert unit” [Eingreifgruppe], that was transferred from Infanterie-Regiment 368 of the 207. Infanterie-Division, is well equipped and armed. This is in contrast with the units assigned to the Division in the month of April, which only barely met requirements; above all the Landeschützen-Bataillonen, Feldkommandanturen and Ortskommandanturen. The equipment is for the most part very deficient and incomplete; the armament is frequently inadequate and furthermore is varied with foreign small arms (Czech, Polish, Dutch, French, Belgian, Norwegian, and Austrian rifles, carbines and pistols); the equipping with horse-drawn and motorized vehicles of all types is, almost without exception, completely insufficient in both type and number for the various expected tasks, and especially in regard to the motorized vehicles, the quantity, condition and type (foreign-made, without spare parts or tires) leaves much to be desired. Very many units, especially the Feld- and Ortskommandanturen intended to be used in static roles, as well as the similarly utilized Landesschützen-Bataillonen and Wach-Bataillonen, are in no way equipped for the anticipated long and distant marches. Even the Divisional command initially had not one single vehicle it was supposed to have.”

This German M40 pattern Feldbluse (field blouse) was made in 1940.

This was offered for sale by a seller who claimed it was an untouched and all-original field blouse, found in an attic. Many collectors scoffed and insisted that because the breast eagle is not a factory application, this must be a jacket that was worn postwar and restored. I saw the typical depot type repairs and suspected that this was a reissued jacket, worn by more than one soldier, in which case reapplied insignia would be normal. I took a chance on it and having it in my hands, I am sure that the insignia are wartime applied, that it was worn like this. The presence of the EK2 buttonhole ribbon and ribbon bar is non-regulation and the ribbon bar could have been added after the war, perhaps even by the original owner (and perhaps not), but I have left it as found.

It is very hard to find an original uniform like this, worn by a soldier in his daily life. Most surviving uniforms were hanging in closets or were in factories, depots or tailor shops at war’s end. Those are the types of uniforms most collectors are accustomed to seeing.

I took these pictures to showcase the various personal and depot repairs to this threadbare and hard-worn jacket.

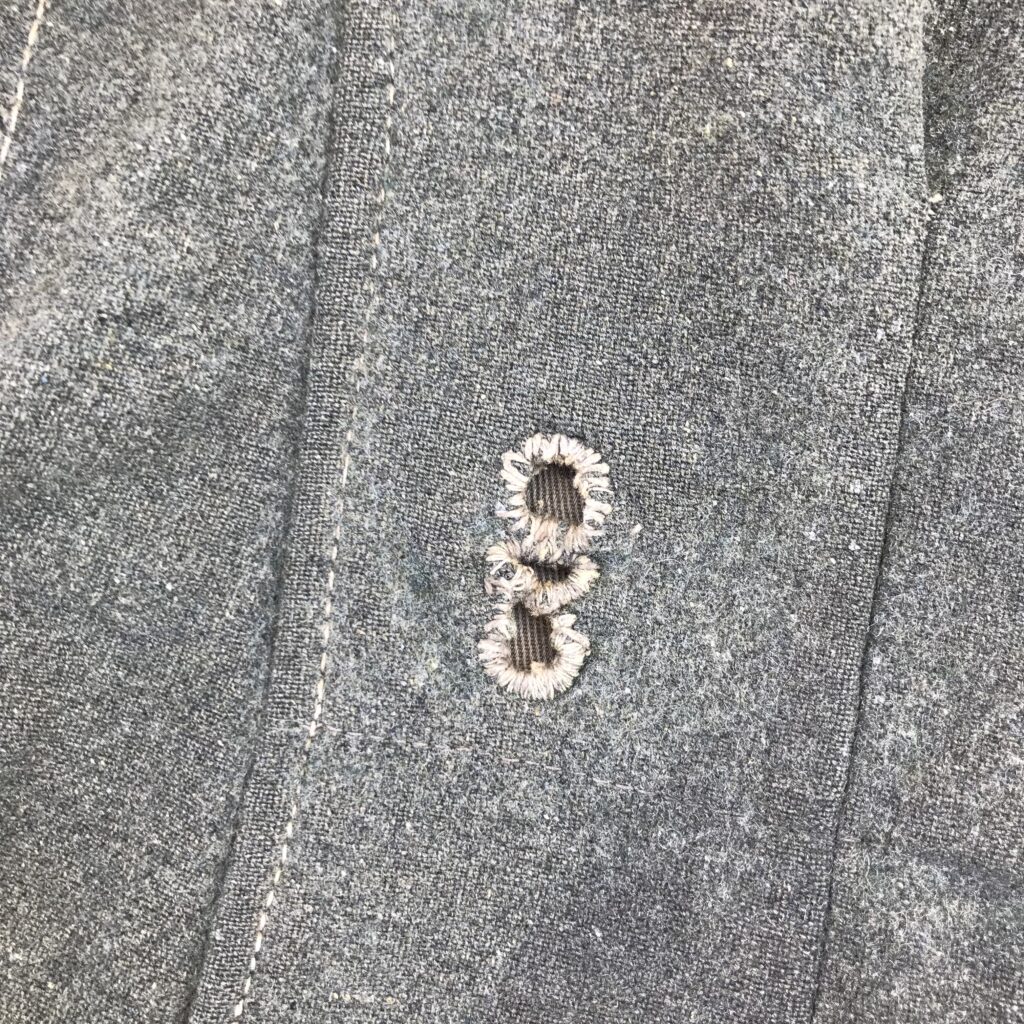

The buttonholes have been repaired or reinforced, possibly by the soldier himself.

One corner of one lower pocket was replaced, and a new flap was added to that pocket, in a slightly different color shade. These are depot repairs done to prepare this worn-out garment for reissue.

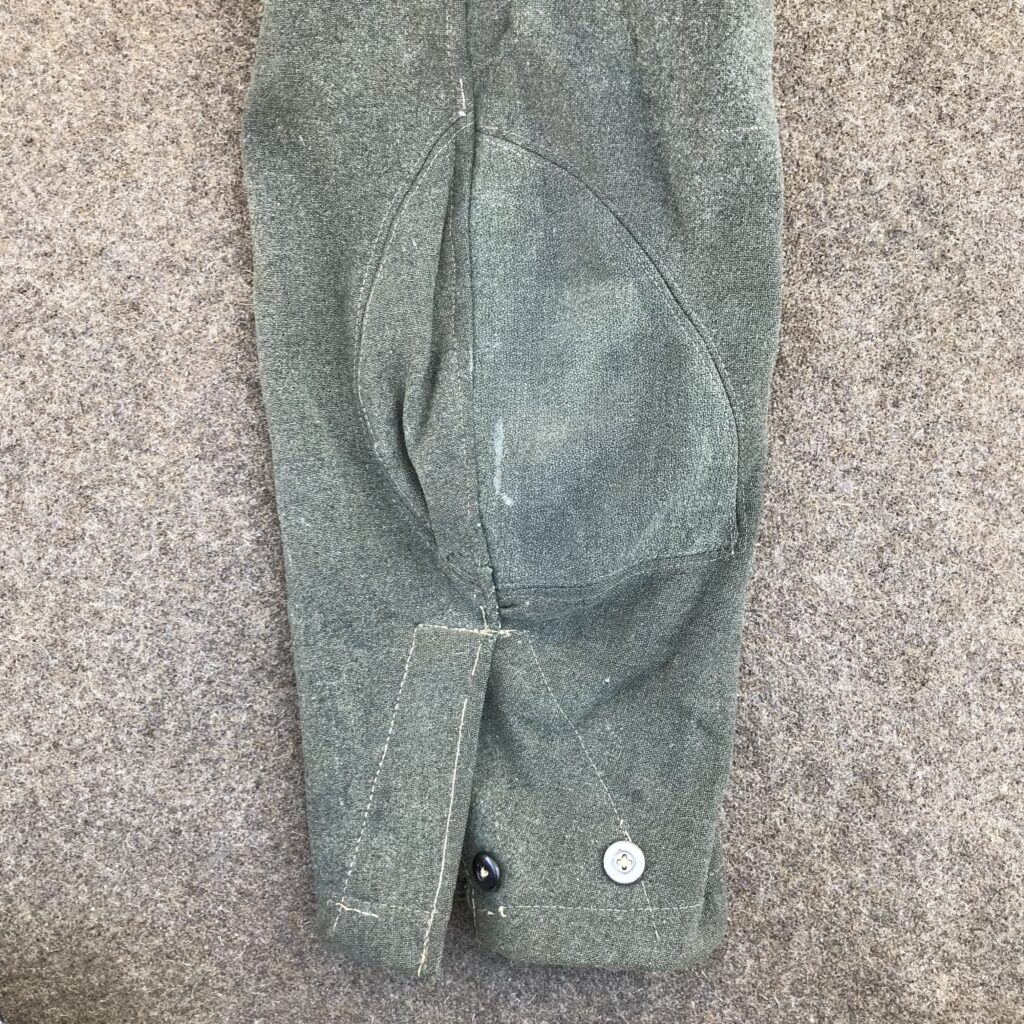

The sleeve ends were altered, with a reinforcing strip of wool sewn to the inside of each cuff. It appears that the sleeves were shortened.

There is a machine sewn repair to a wear hole in one armpit.

Half of one sleeve panel has been completely replaced, as well as the elbow area of the other panel of that same sleeve.

The elbow areas of both panels of the other sleeve have also been replaced. These elbow repairs are all typical depot repairs, seen on reissued items.

Some of the belt hook eyelets are repaired by hand, possibly by the wearer.

-One of the hooks for retaining the internal suspender ends tore off, leaving a hole in the lining. This hole was neatly patched by hand, the edges of the patch neatly tucked underneath, the patch applied with tiny whip stitches.

This photograph illustrates the difference in wear between the exposed collar edge, and the protected wool that was underneath the collar liner (Kragenbinde).

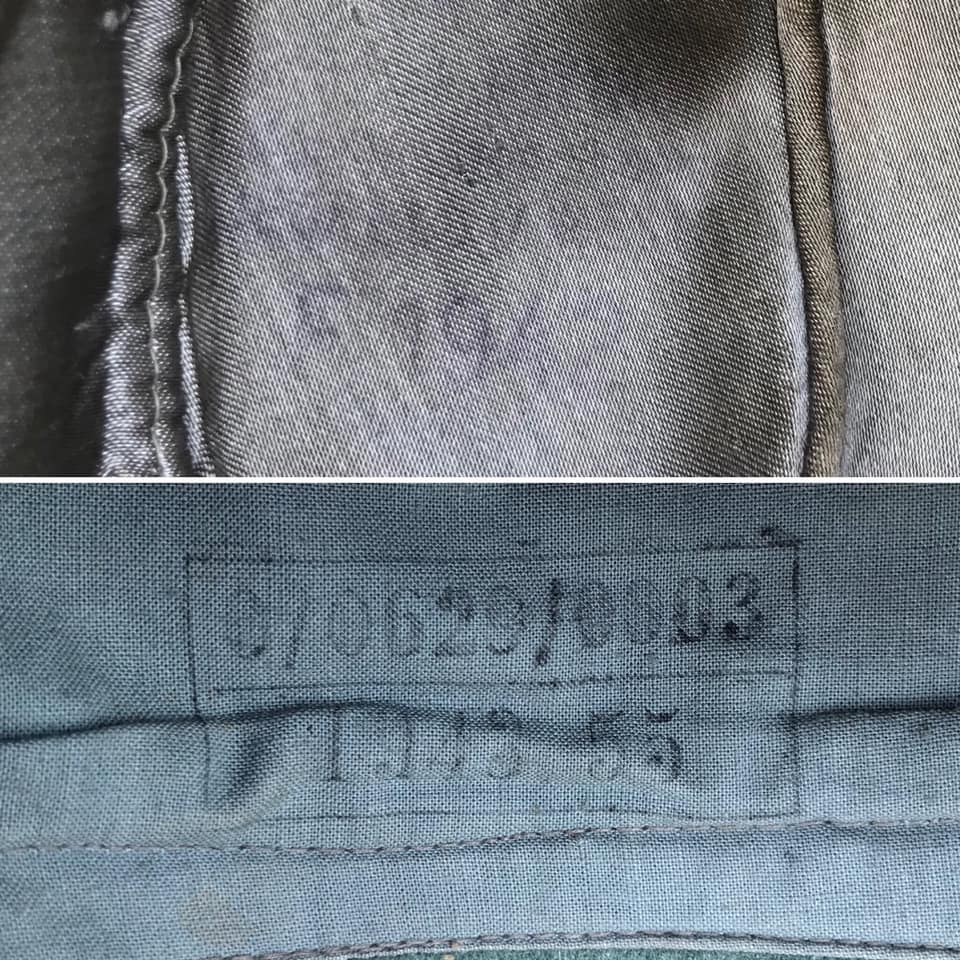

Faded size and depot markings are still visible in the lining.

Many people perceive the 1934 pattern field caps as being early war items, but they continued to be made and issued past the mid-point of the war. The cap on the top (or in the left) in these photos was made in 1942; the cap on the bottom (or right) was reworked for reissue in 1943.

The 1942 cap here is made from typical wartime wool with a rayon lining that is more commonly associated with 1942 or 1943 pattern caps. It has 1940 pattern insignia. The 1943-dated cap was originally an earlier cap that was reworked with new lining panels. Many other examples of this type of reworked M34 cap with replaced lining parts are known, some from the same factory. Usually these have the 1940 pattern insignia, sometimes they have been resized and still have original manufacturer information and dates in the upper part of the lining. This one has a mismatched 1937 pattern cockade with a 1940 pattern eagle. The factory that made this did make M43 caps as well; it’s not that they were a manufacturer who did not change over to the new pattern, rather they were contracted to rework these hats for reissue.

Both of these caps originally had branch soutache, removed after mid-1942. They have machine sewn cockades and hand sewn eagles. Many collectors might regard these eagles as replaced, especially the 1942 example which has terrible stitching. I think both of these eagles are probably original factory applications, and I have my reasons for thinking this, though there is no way to prove it.

There are a lot of differences between these two caps, including the location of the insignia and the height of the front flap. Even on these simple caps with relatively few features, pattern differences are immediately obvious.

There are persistent collector legends about late war made M34 caps with 1944 dates or with factory applied 1943 pattern trapezoid insignia. I have never seen one and if they existed they must not have been common.

Some have asserted that after 1943, the M34 cap was mostly issued to non-combat units, static units or foreign volunteers, etc. This could be true; these units had a low supply priority and got lots of reissued stuff in general. The reworked caps show the effort that went in to keeping these caps in the supply chain. Usable caps were reissued, anything that could be made serviceable was reworked for issue.

In any case, the M34 cap was still evident in huge numbers in 1945, and almost certainly was still being issued (if not actually manufactured) until the last days of the war. Some 1945 film footage of surrendering units shows the M34 cap still predominant.

There may be specific units that can be researched and proven to have predominantly had M43 caps by the end of the war. Beyond that, though, I don’t think an M34 cap in 1944/45 can be said to be wrong. I believe they remained more common than many realize.

This last photo shows 5 original factory made enlisted issue M34 caps, just to give an idea of the range of variation here. Look at the differences in the scalloped front edges, for example. None of these caps have the same ventilation eyelets.

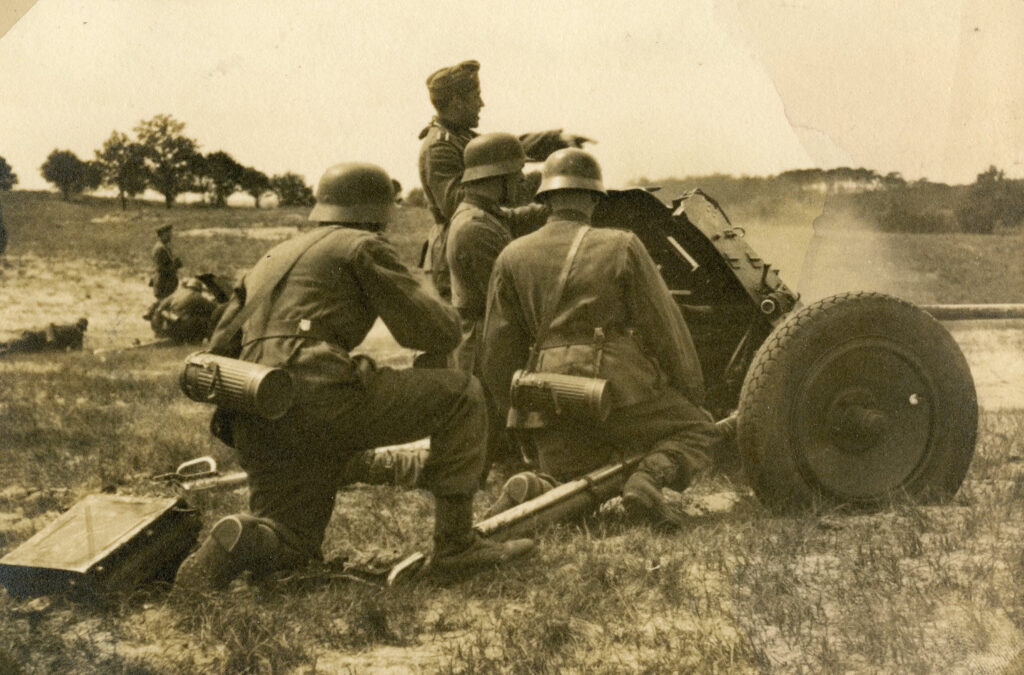

These pictures are from the spring and summer of 1943. They are all from the same album, and document the training of a driver in a Panzerjäger unit, possibly Panzer-Abwehr-Ersatz-Abteilung 3. It’s my experience that private photos from this time are not easy to find, as film was growing scarce by 1943. A notable aspect of this set of photos is that this training unit was using large quantities of prewar and early war kit including M36 tunics, white shirts, white HBT, aluminum belt buckles, M34 caps and even 1934 pattern tunic and cap insignia. Some of the soldiers wear prewar shoulder straps with embroidered Panzerjäger cyphers, and the creator of the album is pictured in a Waffenrock, the use of which had been generally discontinued years before. The photos also show mismatched uniforms and insignia, a captured and reissued Czech tunic, and patch repaired trousers.

I took this set of photos each showing 10 basic German Army uniform and equipment items. I chose the items to be representative of original examples (for the most part). The photos are intended to show variation in original items side by side in the same lighting conditions.

The range of variation seen in the photos is a result of the following factors:

-Changes in materials and construction as the war progressed

-Wear and use

-Modification by/for the wearer

-Patina and toning from age

-Manufacturer variation with regard to construction; variations in raw materials used

Disclaimer: Burning charcoal, wood or similar fuels releases carbon monoxide and other potentially deadly gases that can build up in enclosed spaces and become fatal. Hundreds of people perish every year in the USA alone from carbon monoxide poisoning. This article is about a historical practice and any attempt to replicate this must be done with extreme caution and with full consideration of associated risks and danger.

The use of steel food cans to make expedient cooking and warming devices probably arose spontaneously in many places after cans were introduced in the first half of the 19th century. An interesting description of European peasant use of food can ovens can be found in a novel by Polish author Jerzy Kosiński. Kosiński was born in 1933 and survived the German occupation with help from local villagers. “The Painted Bird,” published in 1965, is a fanciful account of a small boy wandering the Polish countryside during the war, that draws on Kosiński’s own childhood experiences. In the novel, Kosiński describes rural farmers and workers using a device he calls a “Comet,” which consisted of “a one-quart preserve can, open at one end and with a lot of small nail holes punched in the sides. A three-foot loop of wire was hooked to the top of the can by way of a handle, so that one could swing it… Such a small portable stove could serve as a constant source of heat and as a miniature kitchen.” Kosiński writes that “any kind of fuel available” was used including peat, damp leaves and moss, dry twigs, hay and potato stalks. “People always carried small sacks on their backs or at their belts for collecting fuel for the comets. In the daytime, peasants working in the fields baked vegetables, birds and fish in them.”

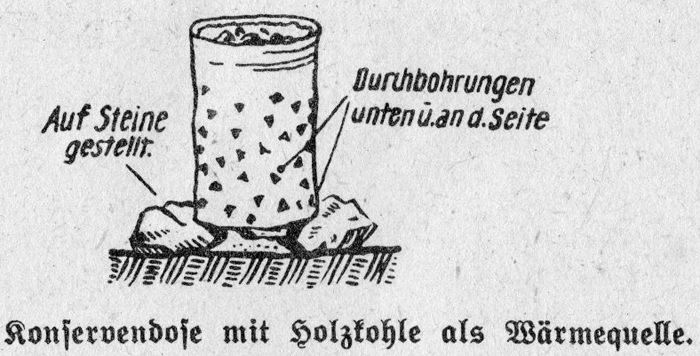

The 1933 booklet “Zeltbau” (Tent Construction), written by Hans Möser and published by Franckh’sche Verlagshandlung in Stuttgart, provides instruction and tips for how to build and live in tent camps, and was probably intended for use by members of the Hitlerjugend and other paramilitary organizations. This text suggests that the “simplest, most comfortable and safest” way to heat a tent is with a “Konservendosenholzkohlenzeltheizofen” (food can charcoal tent heating stove), illustrated below. (“Glücksklee” was a brand of milk.)

“Zeltbau” provides the following instructions for making and using the Konservendosenholzkohlenzeltheizofen: “The lid of an empty food can is completely cut away, the bottom and the lower third of the can are fitted with nail holes, and at the top, on the edge, a wire hanger is attached. We light small charcoal pieces and put them in the Konservendosenholzkohlenzeltheizofen. When the coals are glowing well, the oven is filled to the brim. Every one-and-a-half to two hours (depending on the size of the oven) it is refilled with fuel. The nice thing with this is, that the charcoal pieces burn without smoke and almost without ash (just like with a slow-combustion stove!). The charcoal must in any case be dry. Those with fearful minds fix two wire strips to the outside of the can (only with soldered cans!). In this way you also have the possibility to attach an empty shoe polish tin as a tray for the ash, though this will never fill up. Depending on the ground area of the tent, two to three Konservendosenholzkohlenzeltheizöfen can be hung up.”

The winter of 1941-42 was disastrous for German forces serving on the Eastern Front. The Wehrmacht was ill-prepared for the bitter cold temperatures of the Russian battlefields. In the battle for Moscow, there were more casualties from cold than from combat. About 250,000 German soldiers suffered frostbite in that freezing winter. As part of a plan to prevent a repeat disaster the following winter, in 1942 the Wehrmacht issued a handy little book called “Taschenbuch für den Winterkrieg” (Paperback for the Winter War) which featured extensive information about winter camouflage, clothing for keeping warm, maintenance of equipment in low temperatures and other subjects designed to help German soldiers live and fight in the Russian winter. The following excerpt from this manual discusses ideas for improvised heat sources.

“The ability of the soldier to resist the cold is considerably strengthened when as many as possible opportunities to get warm or to stay warm can be achieved, especially for the feet of sentries. Even field positions, bivouacs and emergency lodging can be sufficiently heated with simple equipment or self-made devices. Even a stopgap heater is better than none at all.

The following can serve for warmth:

-Candles

-Lamps

-Cooking equipment (alcohol, benzene, petroleum)

-Warming fires

-Hot stones, etc.

-Field ovens

-Lodging ovens

-Walled-up ovens

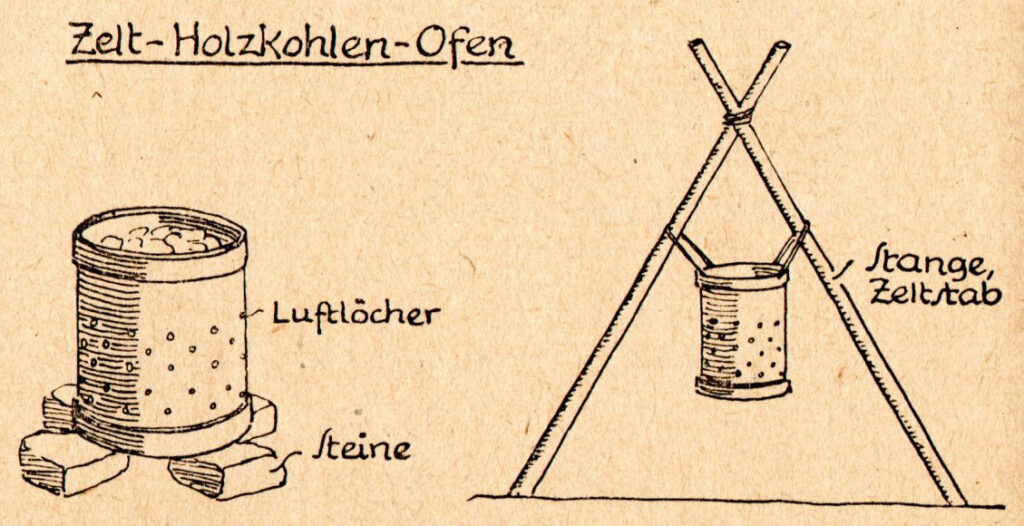

Tents, snow bivouacs, etc. can readily be heated with candles, lamps or cooking equipment to a reasonably tolerable temperature. Food cans or marmalade buckets poked through with holes and filled with glowing ashes or wood coals also provide a good, handy heat source (see illustrations). Development of harmful gases must be looked out for (follow operating rules exactly!). Through covering, the melting of snow over the candle etc. can be hindered.”

The text is accompanied by two illustrations that show improvised tin-can heaters. The first shows a hanging tent oven made from a marmalade bucket suspended from tent poles. The second illustration shows a food can, placed on stones, with charcoal as fuel, used as a heat source. Both cans have many holes poked in the sides and bottom.

“Tornister-Lexikon für den Frontsoldaten” by Gerhard Bönicke was a book of tips for life in the field that was published by the Wehrmacht for distribution to soldiers in 1943. This book includes instructions for the same type of tent charcoal oven in the section of the book dedicated to expedient oven construction. “For the combustion of charcoal, use a bucket without a lid, with air holes on the sides and bottom as shown. The bucket is placed on 3 or 4 stones or is hung on three tent poles.” This book also provides instructions on how to make charcoal for use as a heating fuel.

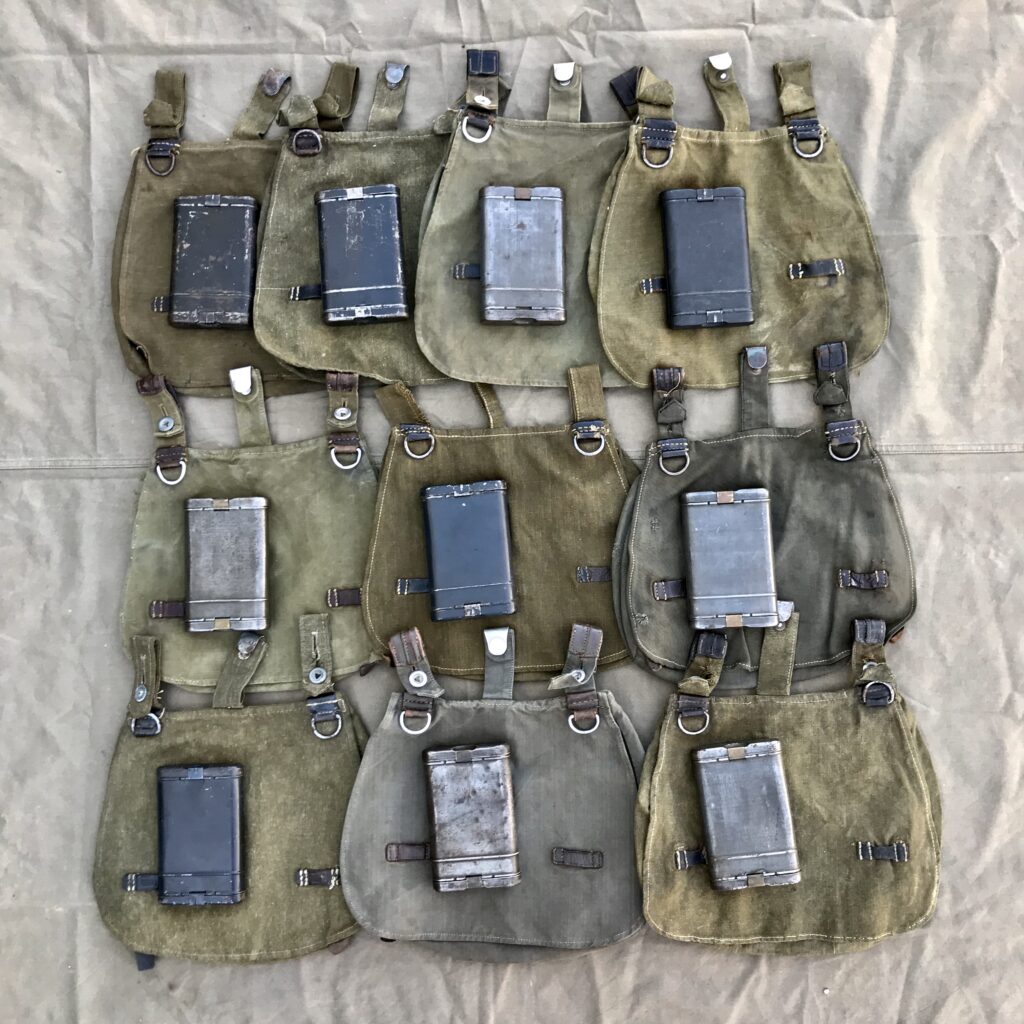

How big was a food can or marmalade bucket? Food cans came in various sizes, of course, but a common size of Wehrmacht issue food can is shown below, together with a circa 1930s German marmalade bucket that is the same size. Both the can and the bucket are about the same size, about 4 inches in diameter and about 4-7/8 inches tall. The straight sides (no ribs) are typical for steel food cans from that era.

To find out how well a food can stove of this size might heat a tent, I used this postwar (1950s or 1960s) West German plum jam bucket that is the same size as the cans shown above. I used a nail to poke the air holes in the sides and bottom, based on the illustrations in the texts. The round nail pokes square holes. I put a piece of round wood inside the can to support it while driving the nail through, and used the round surface of the hammer to push out any minor dents that occurred.

For fuel, I used lump charcoal. After the charcoal was burning I left the stove outside for a while until most of the paint was burned off the metal. I then placed the stove on rocks inside a four-panel pyramidal Zeltbahn tent, a small tent that would have housed four crowded soldiers in WWII. I used only four tent stakes to affix the stove to the ground, and it was a cool, very cloudy, breezy day, with light drizzle. I hung a thermometer in the tent on the opposite side of the stove. The stove burned well, the charcoal gives off a lot of heat and burns for a long time.

After 30 minutes I checked the thermometer. The outside temperature was a cool 53 degrees Fahrenheit. Inside the buttoned-up tent, the temperature had risen to a balmy 80 degrees Fahrenheit!

I let the stove burn out and cleaned off the paint residue. At a future time I might get a carbon monoxide monitor and run another test to learn just how deadly this thing might be.

It is easy to see how this useful little stove could have had myriad applications in the field. My test suggests that these little stoves could have kept fortunate soldiers reasonably warm even in the bitter cold.