WWII German reenacting needs a certain number of people worldwide for vendors to be willing to supply products that are mass-produced and economical, and for there to be enough people for there to be large events, and events at certain places. The more participants at an event, the more money an organizer (generally) has to make things happen. Those of us who are reenactors should all want to see the numbers in this hobby grow. Even if you view yourself as a super hardcore guy who scorns more laid-back units, the reality is that most reenactors start in mainstream type groups, and these guys are your pool of potential future recruits for the most part (not to say you should ever actively recruit from other units as this is “poaching” and very bad form). The bottom line is that there is no credible argument that less reenactors is better. The more people there are, the more people will be running events and finding event sites and doing the stuff people need to do for the infrastructure of this hobby to exist. A RISING TIDE FLOATS ALL BOATS.

The number of people involved in reenacting is always changing, it goes up and down. Some people are always going to leave due to moves and career changes, divorces or because they simply lose interest. That’s unavoidable. Recently the reenacting hobby has also had to deal with some additional external political pressure, that has certainly caused some people to leave reenacting. Reenactors should be proactive and do what we can to counteract this.

The best way to increase numbers is probably to beat the bushes and find new members for your unit in your local area. But that’s not the only way. It is my belief that it is possible to broadly promote WWII German reenacting as a hobby, via social media. In today’s world, this does entail some risk. Here are the strategies I have been using to do this. Have they worked? I can’t prove it, but I think so. I certainly don’t think it has hurt. I think if other reenactors would get on board and use the same or similar tactics it would be much more effective.

My strategy has two basic components:

1. Get great photos at events and share them as widely as possible.

2. Be an ambassador for the hobby and a public face and point of contact on social media even if your real name and identity are concealed.

1. Photos

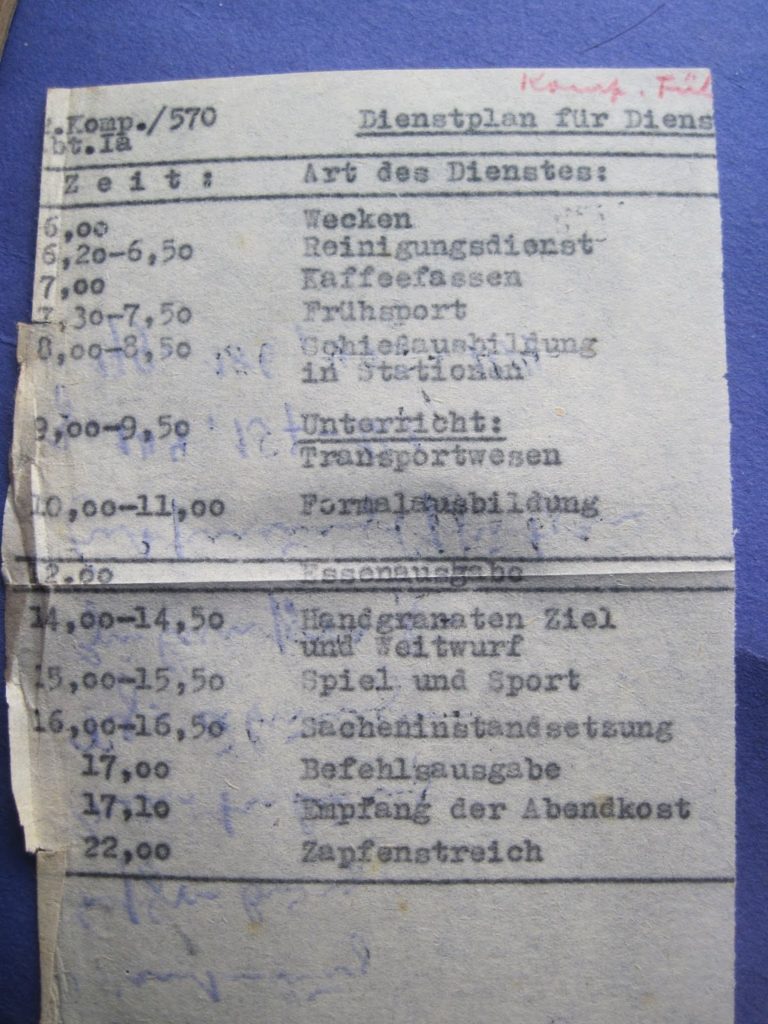

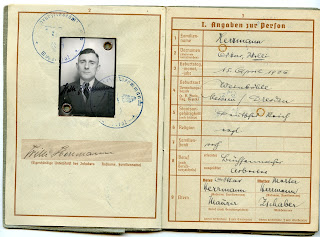

Part of the reason why I got into this hobby in 2000 was from one single photo that looked so good. This guy looks super real, and looks like he is having fun.

Look at reenactment photos you think are great. Figure out what you love about them and either take photos like that, or identify a guy in your group who can take the photos. When you are out on the battlefield, or inundated with spectators, you are not going to want to pull out a modern camera or phone. Maybe set aside some time before the event, after you are set up. Or after the public goes home. Or at the end of the event. It doesn’t have to take much time to make some great images. Ideally you want to get pictures that showcase not only your group, but the good things about the event site that make it unique and special. If you have a period camera, or if you are in a situation where it won’t destroy the setting if you pull out a digital camera, you can take some in-the-moment candid shots. Most wartime photos, though, were staged or at least posed in some way. A thought out photo is always going to be more impactful than unflattering candid shots of people eating (for example).

Once you’ve got the photos, comb through and select only the best ones. Never post a photo with some modern thing in it and caption it “Apologies for the modern vehicles” or whatever, this is embarrassing and may well end up being shared elsewhere without your explanatory caption. If you can’t crop the farb out, share it with your unit, but not with the world; images should stand on their own merits. Only post around 5 photos maximum on social media at a time. Social media is designed for instant gratification and short attention spans. Most people don’t want to scroll through two dozen pictures of your guys pointing rifles; if you post big sets of photos many people will be overwhelmed or lose interest and the impact is diminished. Sometimes you will only get 3 good pictures from an event. Other times you might get 30. In that case, you need to space out posting these. Post a small batch of around 5 photos each day. Separate them into unique batches that highlight a specific aspect you can talk about. Post the pictures on your reenacting-specific Facebook account if you have one (and you should). There are lots and lots of WWII reenacting and historical discussion groups on Facebook where you can post the photos. Don’t spam these groups, do one post only with a few of the very best photos and a description of the event. Maybe post in one group one day, and make a different post with other photos in a different group a day or two later. You never know where your photos are going to find the one guy on the other side of the world who is going to be so blown away he immediately jumps in with both feet. Your unit should also have a public Facebook page and also maybe a web site. You could also look around and find Internet forums with active memberships where you could post this stuff. Make sure your members are OK with having their photos shared. Some may not be, and that’s understandable. There are ways to show people where they are not going to be recognized. Use some creativity. It is always best if you can share any photos without revealing your actual name/identity.

I will often post event photos on social media in a very specific manner that I believe drives interest. As soon as I am set up at a reenactment event I will post one photo that shows some aspect of how we are set up, or where we are. This makes some people wish that they had attended that event or that they were going to some other reenactment at that time. Right after the event, on Sunday, I will post what I feel is the best digital picture that came out of that event. Then, over the next week, I will post the rest of the digital photos, and eventually the film photos, in small batches.

Instagram: You might want to have a personal reenacting Instagram account and one for your unit. I have come to regard Instagram as evil and insidious. Your phone has some way of figuring out what Google/Facebook/Instagram accounts you have and showing your various Instagram accounts to people you interact with elsewhere. A private Instagram account has no promotional value but a public one entails some risk if there is a chance there could be someone who will use this against you. On our unit Instagram we never show any close-up portraits or any photos in which anyone is easily identifiable at a glance. Lots of group shots, photos of the camp, photos taken from behind a marching column, etc.

Facebook or Instagram could delete any profile or group at any time, just for posting historical content related to WWII Germany. Back up stuff you want to keep.

2. Being a hobby ambassador on social media

You want to act as a cheerleader for the hobby, how ever and where ever you can. If you love an event, post on social media about how great it was. Go in the event group page and say what a good time you had. If it’s an annual event, when it is coming around again next year, post a highlight photo from the year before and talk about how great it was. You will be helping to promote the event. Event organizers appreciate this.

If an event sucks, don’t go back. Maybe some other people or groups like it, let them like it. Don’t disparage those events in an attempt to promote the events you do like. It’s a bad look.

Try to find spaces online that are open to reenactment discussion and post about your group. This is not just self-promotion. It promotes the hobby as a whole, everywhere.

Try to keep it professional and positive at all times. Don’t throw shit at other reenactors in public. Potential recruits could see this and get the wrong idea, it could turn them away. Nobody wants to wade into a morass of name-calling. Keep reenactment drama off the Internet at all times. Keep it private and go through the chain of command. Airing dirty laundry in public on social media is NEVER productive.

Find social media accounts for reenactment groups and follow them. Like their posts and comment on them. This makes them visible to a wider audience, it’s how the algorithms work. If you can’t say anything nice, just hold your tongue. But really, even with a total clown group, you should be able to find some little thing to appreciate.

Saying bad things about the hobby as a whole is not being a good ambassador. You want to talk it up and promote it. That’s not to say that you can’t go to a reenactor discussion group on Facebook and comment on stuff that is too heavily represented, or dispel myth and lore. That’s fine and good. But nobody wants to read about how reenactors are too old/fat/drunk/farby/real Nazis. If you feel like you need to vent, call a buddy from your group, or just back away from the computer for a bit and clean your rifle or something, until the urge passes.

Don’t post modern political stuff on reenactor accounts and ESPECIALLY don’t ever post anything that could be construed as “racist” by people trying to make you look bad. Even if it is an obvious joke (to you). They will hang you with this stuff. This makes us all look bad when they inevitably find you and make a stink about it.

At all times: share good information, lead by example, be the change you want to see in the hobby.

If you are not already a WWII German reenactor and you have read all this way, you should get started. It’s a ton of fun and you will make new friends and you won’t regret it.