Our impression is based on an isolated, rear area, security outpost. Essentially we are combat ineffective, and passive defense is all we have to offer. One means of soft protection is through the use of booby traps. These were commonly used by the Germans during WWII, especially when abandoning a position, in retreat, or as means of passive defense. This blog post is an introduction to WWII German booby traps.

Introduction: A booby trap is an explosive or non-explosive device or other material, deliberately placed to cause casualties when an apparently harmless object is disturbed, or a normally safe act is executed, or a normally safe place is occupied. They are not offensive weapons, and no battle, let alone war, can be won with booby traps. They are defensive weapons. They can provide early warning of a foe’s approach. Their main contribution is psychological, and a slowing of the enemy’s advance. For non-combat reenacting purposes, setting (non-active) booby traps is a very “zoney” experience for immersion settings.

Activation: Booby traps are activated by one of a few means. These are the most common forms of bobby trap activation.

Pull Release: A basic trip wire. An explosive charge is anchored, and wire is attached to some other object. A pull on the wire releases a firing pin in the explosive. These are mostly German stick and egg grenades (activated via trip wire).

Tension Release: When wire is cut, broken, or released

Pressure: Adding weight to an object

Pressure Release: Removing weight from an object

Lever Release: Fuse activated by pulling a safety/arming pin. An “enticing” object is placed on top of a grenade with the lever removed. The “enticing object” has just enough weight to keep the release lever in place. Once the object is moved, detonation occurs. Many Russian and Allied grenades were this style, and could be used in this fashion.

Placement: The Germans excelled at predicting enemy thought processes in order to develop unpredictable booby trap situations. One famous example involved a crooked painting on a wall. The Germans anticipated that only an anal retentive Officer would want to straighten a crooked wall hanging. They were correct. When an Allied Officer straightened the photo, movement of the picture frame activated a booby trap, and killed him. This illustrates that the key to placement is to think ahead, to anticipate how people interact with their environment, and to place traps that mesh with those actions. That said, there are some general principles that serve as guidelines to where, and how, booby traps should be placed and positioned.

Booby traps are most effective when used in small, confined, spaces. In such spaces there is a higher chance of activation, and greater explosion impact. Examples of such spaces are passages, stairways, doorways, smaller foxholes, narrow paths, etc. Items of curiosity are also great choices: souvenirs, containers, jewelry, food, water, gasoline containers, “abandoned” weapons, etc. Everyday operations can also be nefarious booby trap locations. Opening a window or door, flipping a switch, picking up a phone receiver, etc. The Germans booby trapped almost every conceivable area, and type of moveable object, with assorted prepared charges.

In Roadways

-Obstacles in road / near roadside (Very common. Some type of obstacle is placed in road. Log. Barrel. Vehicle. Anything. It is booby trapped to explode when moved. A field of fire can also be set up on the roadblock.)

-Embankments

-Blind bends

-Bridges

-Culverts

-Wooded stretches

-Junctions

-Crossroads

-General debris

-Shoulder of roads (sharp corners), where vehicles/foot solider may swerve off main road

-Near roadside houses or obvious turnouts, where vehicles are likely to pull over, or parking areas

-Entrance to detours

-Railroad crossings

In Open Country

-Woods

-Trees

-Low branches of brush

-Posts

-Gates

-Fences

-Paths

-Hedges

-Obstacles

-Stores

-Dumps

-General debris

-River fords/banks

In Buildings

-Steps

-Floors

-Doors

-Windows

-Cupboards

-Ovens

-Passages

-Furniture

-Fireplace

-Wood piles

-Water traps

-Closets

-Supplies

-Telephones

-Light switches

-Floor coverings

-Pictures

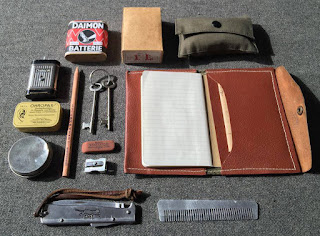

-Documents

-Debris

-Loose floor boards

-Rugs

-Flashlights

-Cigarette Cases

-Pens

Assorted

-Bodies of dead

-Soap

-Jerry Cans

-Food/Water

-Fishhooks hanging dark pathways (inside or out)

Use of Dummy Traps: Dummy booby traps (e.g. inactive) can effectively be used, especially if a few are “obviously” placed to ensure they will be found. Once they have been detected, the enemy will not know which traps are real, and which are inert. He will be extra cautious, and investigate/avoid all that looks suspicions, which will delay his advance. This can help create the illusion of a much stronger defense than is actually present, which can be greatly beneficial to thinly occupied areas. Multiple live, and dummy traps, can be placed in a concentrated area. Inaccurate signs can also be used to further create confusion (e.g. a sign indicting area is mined, when it fact it is not, or vice versa).

Detection: Of course, booby traps can also be used against your own forces, especially by partisans. Being acutely aware of your environment can aid in detection. Below is a list of things to watch for.

-Moveable objects: equipment, souvenirs, etc.

-Minor obstructions of all kinds on roads

-Be very suspicious at sabotage locations. Cut wires, road obstructions, blown bridges/tracks, etc., all which must be repaired are often booby trapped (esp. sites of cut communication lines).

-Inside trench systems, fox holes, in buildings, etc.

-Disturbed ground, esp. after rain

-Explosive wrappings, sawdust, nose caps from shells, etc.

-Traces of camouflage, withered vegetation

-Breaks or disturbances in vegetation, dust, paintwork, timbering, etc.

-Presence of pegs, nails, electric leads, pieces of wire or cord where there is no apparent use

-Marks on trees, paths, the ground, walls, etc. where there is no apparent reason

-Booby traps will not often be found in inaccessible places. If you make own trail, you will be safer.

-Irregular tracks of foot/wheels traffic where no apparent reason

-Any indication that an area has been carefully avoided

-Any indication of attempted concealment, or indication of all too obvious objects

-Anything out of the ordinary may indicate a booby trap

-Everything movable, seemingly harmless, and enticing should be treated with caution.

Avoidance: To avoid booby traps, avoid obvious actions (e.g. going through a doorway when there is another option, climbing over an obvious break in stone wall, etc.). These are prime locations for booby traps, as typical human behavior/actions are very predictable in such settings.

-Avoid obvious, well-used path ways

-Climb over low walls rather than use gates

-Check ditches and foxholes rather than just jumping in

-Enter buildings through blasted holes/windows rather than doors

-Be suspicious of anything enemy left behind

-Touch nothing that appears enticing

FUSES

Two of the most common fuses for booby traps were the Z.Z. 35 (pull activation) and the Z.u.Z.Z. 35 (pull and release activation). These can be used in conjunction with egg grenades, S-Mines, teller mines, box mines, and stock mines.

Eihandgranaten 39 (Eihgr. 39)(Egg grenades)

The Eihandgranaten 39 is especially useful for booby traps. When the cap is unscrewed, a pull cord is revealed. Fasten a tripwire to this, or equip with a Z.Z. fuse. Blue capped grenades had a 4.5 second delay. The red caps, used specifically for bobby traps, had a 1 second delay. The types with “protective ears,” and a carrying ring, serve well as securing anchors when used as booby traps.

Illustrated Examples

Two teller mines connected by a Z.Z. fuse. Removing one will activate the other.

S-Mines were also very common for booby traps.

Teller mine equipped with two Z.Z. fuses.

Weight of Teller Mine keeping activation lever of grenade underneath in place.

Box mine. These were often pressure activated, but could also be set up with wires.

S-Mine with Z.Z. fuses.

S-Mine with pressure activated fuse.

Stock Mines with Z.Z. fuses.

Sources for info and photos:

Instruction Manual for the Infantry, H.Dv. 130/2a

Der Rekruit, 1935

Handbook on German Military Forces, TM-E 30-451, March 1945

World War II Axis Booby Traps and Sabotage Tactics, Gordon L. Rottman

.jpg)

.jpg)